A handful of people turned out Saturday afternoon for a workshop sponsored by the Sag Harbor Village Board on accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, which have been viewed as a simple, decentralized approach to addressing the affordable housing crisis — but which, so far, have proven difficult to implement.

Mayor Tom Gardella, who called the public workshop, said his goal was to “make this process as smooth as possible,” particularly for residents who already have a garage or other structure on their property that can be easily converted into affordable housing.

In 2020, as part of a broader effort to promote affordable housing, the Village Board passed a code amendment that made affordable accessory units legal with just Building Department review, and it reduced the minimum required size from 500 to 280 square feet in 2023.

Elizabeth Vail, the village attorney, said when the village first adopted the accessory apartment law, it sought to limit the number that could be built by requiring that a lot be at least 70 feet wide.

But since many properties in the village don’t meet that threshold, their owners found themselves being required to go before the Zoning Board of Appeals to obtain a variance if they wanted to convert an existing structure into an ADU.

Anthony Vermandois, an architect whose practice involves numerous village renovations, said the required lot width was mostly affecting residents who have a preexisting structure they want to convert, noting that often those buildings don’t need to be enlarged or require variances to be converted into ADUs.

Bruce Schiavoni, the village code enforcement officer, presented a report that seemed to back up Vermandois’s opinion.

Schiavoni differentiated between accessory apartments, which are attached to an existing house, and accessory dwelling units, which are standalone buildings.

The village has received five applications for accessory apartments, three of which have been approved, he said. But of eight applications to convert existing structures into ADUs, six require lot width variances, he said.

A measure that would eliminate the 70-foot width is currently before the board, but the workshop was scheduled to allow residents and board members to suggest other potential changes.

Alex Mattheissen, a member of the Village Zoning Board of Appeals, who spoke on his own behalf, said he was able to remain in the village only because he lives in a preexisting cottage on his property and rents out his main house.

He urged the village to loosen restrictions so property owners would be able to live in accessory apartments and rent out their main houses.

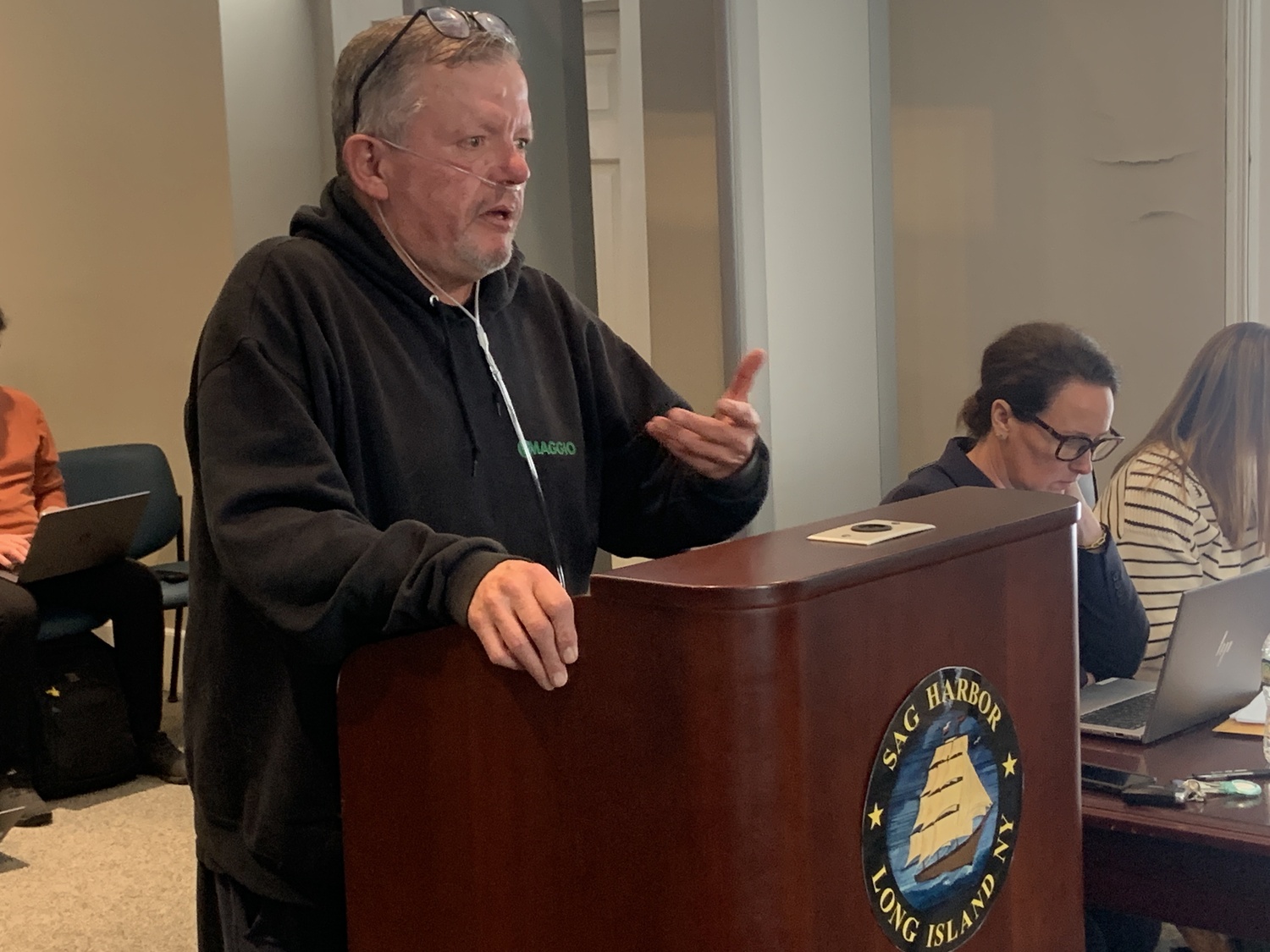

Ralph Ficorelli, a resident of Joel’s Lane, is a homeowner who finds himself in no man’s land. Ficorelli told the board he wanted to convert his garage into an accessory apartment and had been told after a two-year wait that he couldn’t get a permit because his property is only 50 feet wide at the street. Ficorelli, who is disabled, wants to move into the unit himself so he would not have to climb stairs, but he learned under the current rules that would not be allowed.

The board said it would consider amending the law to allow residents to move into their accessory apartments.

Board member Aidan Corish suggested the board put a sharper point on what it wants to accomplish and raised the concern that residents could find themselves surrounded by twice as many neighbors as they had before.

“How do you balance the needs for workforce housing with the needs for people in the village who may be surrounded by four or five accessory structures?” he asked. “All of a sudden, instead of four neighbors, they have eight.” He questioned how the village would address parking, emergency responses and quality-of-life concerns.

The board is expected to resume the discussion when it meets next month.