Representatives of Sag Harbor’s traditionally Black beachfront communities appeared before the Village Board on Tuesday, August 9, to make their case for the creation of a special zoning overlay district for the Azurest, Sag Harbor Hills and Ninevah neighborhoods.

They believe the move will help protect both the character of their communities and the property rights of homeowners without the restrictions that a historic district could impose.

Errol Taylor, the president of the Ninevah Beach Property Owners Association, said the proposal to adopt zoning restrictions for the neighborhood to limit house sizes and the number of accessory structures was supported by more than 95 percent of residents, who voted 204-10 in favor of establishing an overlay district in a recent survey.

He said the proposal was honed by the Tri-Community Working Group, made up of the three developments’ presidents and 14 other residents, over the last year and a half. The committee looked at similar communities. “We met with everyone who would meet with us,” he said. “We did our homework.”

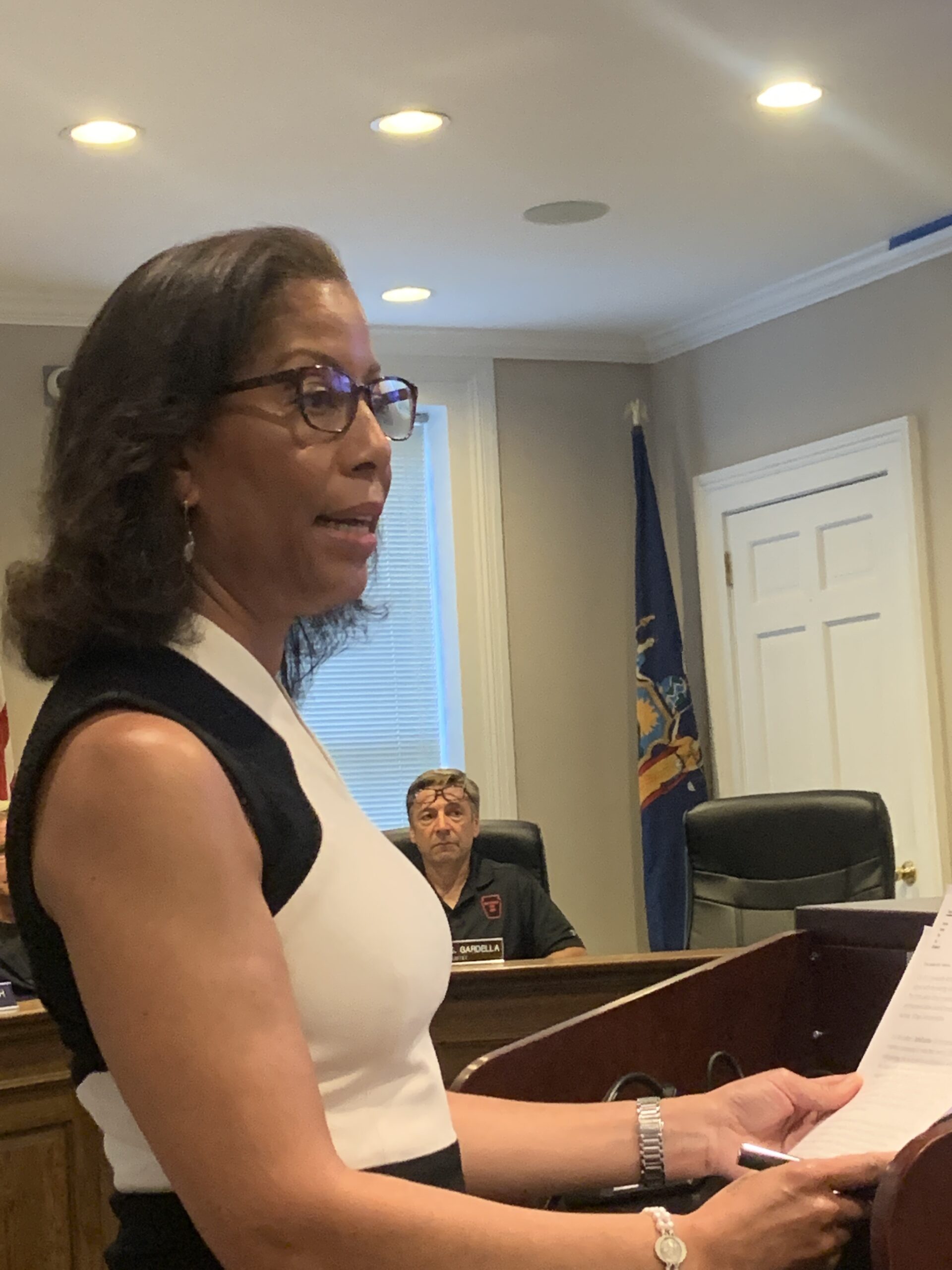

Although the board has yet to schedule a formal hearing on the proposal, it heard detailed explanations from Taylor and Lisa Desamours, president of the Sag Harbor Hills Improvement Association. Steve Williams, president of the Azurest Property Owners Association, also took part in the effort, although he did not speak at Tuesday’s meeting.

The board also heard a rebuttal from Georgette Grier-Key, the director of the Eastville Community Historical Society, who urged the board to continue to weigh the advantages historic district protection would provide.

Grier-Key also read a letter from Renee Simons, a Sag Harbor Hills resident and member of the SANS organization, who has been a strong advocate for a historic district.

Mayor Jim Larocca, who had placed the item on Tuesday’s agenda for discussion, said the board would consider both requests.

The effort to create the overlay district grew out of an earlier push to have the three neighborhoods added to Sag Harbor’s historic district, or made into a new historic district, largely because of their cultural significance as places where Black people were able to buy property and build vacation houses in the post-World War II era, often self-funding their efforts because of racist lending practices.

Calls to protect the neighborhood with a historic district began when speculators began to target the neighborhoods because they could find inexpensive houses to tear down and replace with much larger ones.

Although the neighborhoods have received state and federal historic designations, they have yet to be designated as a village historic district. That was derailed after some residents voiced fears that such status would restrict their ability to replace or renovate their homes and unlock the value of their underlying real estate.

When the neighborhood associations sponsored public forums on preservation efforts, “not a single person said it was the architecture, not a single person said it was about saving the bungalows dotting our neighborhoods,” Taylor said. Instead, he said, their interest was directed at finding ways to protect the character of their neighborhoods, where people enjoy a comfort level that comes with knowing their neighbors.

Desamours said the overlay district would be built on three pillars: stabilization, enforcement, and representation.

To stabilize the community, the overlay district would impose a strict 4,000-square-foot size limit on house size, no matter how large the lot, and limit to two the number of accessory structures that could be built, no matter how large the lot size. Special uses, such as a bed-and-breakfast, would be prohibited, and clearing restrictions strictly enforced.

To help with enforcement, applications for variances or other village review would require that property owners notify their neighbors, as is the case now, but if the steps were not taken in a timely manner, the board hearing the application would be required to postpone the application to a future meeting.

Residents would be permitted to submit photographs of alleged violations to village enforcement officers to trigger an investigation, and the association presidents would meet quarterly with village enforcement officers, to foster a working relationship.

Finally, although Desamours acknowledged that a growing number of residents from the neighborhoods have been appointed to village regulatory boards, she said the time had come to codify the practice.

Not everyone was in agreement that the overlay district would be the best course to follow.

Grier-Key read a lengthy letter from Simons, an early champion of the historic district, outlining efforts to protect the character of the community dating to 2016.

She argued that the overlay approach, based largely on existing code, ignored the ability of a historic district to prevent “erasure or elimination of an area over time,” would allow unlimited demolition, and would not be permanent and could be undone by a future board.

In her own remarks, Grier-Key said as state certified local government, the village was required to move forward with efforts to protect historic resources and asked why the village Board of Historic Preservation and Architectural Review had failed to act on the SANS request.

Sarah Kautz, preservation director for Preservation Long Island, also spoke, saying that the organization supported the idea of an overlay district but adding that the village’s ability to create historic districts could achieve the same, if not better, results.