On October 2, 1819, Cato Crook, a former slave who lived in Bridgehampton, wrote a letter to Elias Smith, a wealthy landowner in Smithtown, asking that his enslaved niece, who had run away from Smithtown and sought refuge with him, either be treated better or released from servitude altogether.

That letter, which is in the Smithtown Library’s collection, along with entries in a family Bible in the Hampton Library’s collection, and a smattering of details from census records, are about all that is known of Crook.

On Sunday, Julie Brennan Greene, the Southampton Town historian, sought to piece together a better portrait of the man and that period in Southampton history from those fragments in a lecture, “From the Pen of a Former Enslaved Man,” sponsored by the Bridgehampton Museum to mark Black History Month.

By now, just about everyone should know that, yes, slavery was once legal in New York State. While many other northern states banned the practice, New York was a holdout, waiting until 1799 to pass the Gradual Emancipation Act. It freed all slaves born after July 4 of that year, with the lone caveat being that women had to remain in servitude until they turned 25 and men until they reached the age of 28. A second law in 1817 extended freedom to those born before July 4, 1799, but not until 1827.

Crook, who was born in 1763 and died in 1841, was freed by his owners, Herrick Rogers and Micah Herrick, in 1817. The circumstances surrounding their decision are unknown. But as part of that process, his former owners had to guarantee to the town’s overseer of the poor that he was capable of fending for himself and would not be a burden to the town’s taxpayers, Greene said.

Slavery was fairly common throughout Southampton Town right up to the early 19th century. The earliest mention of a slave in town records occurs in 1660, Greene said, when a man known simply as “Peter” is listed.

In a 1698 census, the town’s population was recorded as 821 people. Of that total, 83, or about 10 percent, were slaves. There were 40 men and 43 women. Although slaves were named in that early census, only their first names were used, Greene said.

While most worked in farming, slaves typically had other skills, including tailoring, blacksmithing and whaling for the men, and cooking, housekeeping and child care for the women.

By the 1790 census, there were 145 slaves in town, and 30 people remained enslaved as late as 1820, although by that time the census showed a population of 187 free Black people.

In his 1819 letter to Smith, a descendant of Smithtown’s founder, Richard Smith, Crook indicates that it is not the first time that his niece, whose age was not recorded, had run off and walked to his farm on Scuttle Hole Road. As he did not want to be accused of illegally harboring her, Crook sought direction and offered his advice.

“She complains much of hard usage, which if it be true, ought not to be,” Crook wrote, “and, as she is uneasy and has gotten into the habit of leaving you, I wish, sir, that you would dispose of her.”

“Crook’s letter is remarkable for several reasons. First, because of the forward-thinking content, but also because the author was clearly educated,” Greene said. “A letter written by a newly freed enslaved person to a man of authority was unheard of. This was one of the very few 19th century letters written by an African American known to exist in Suffolk County.”

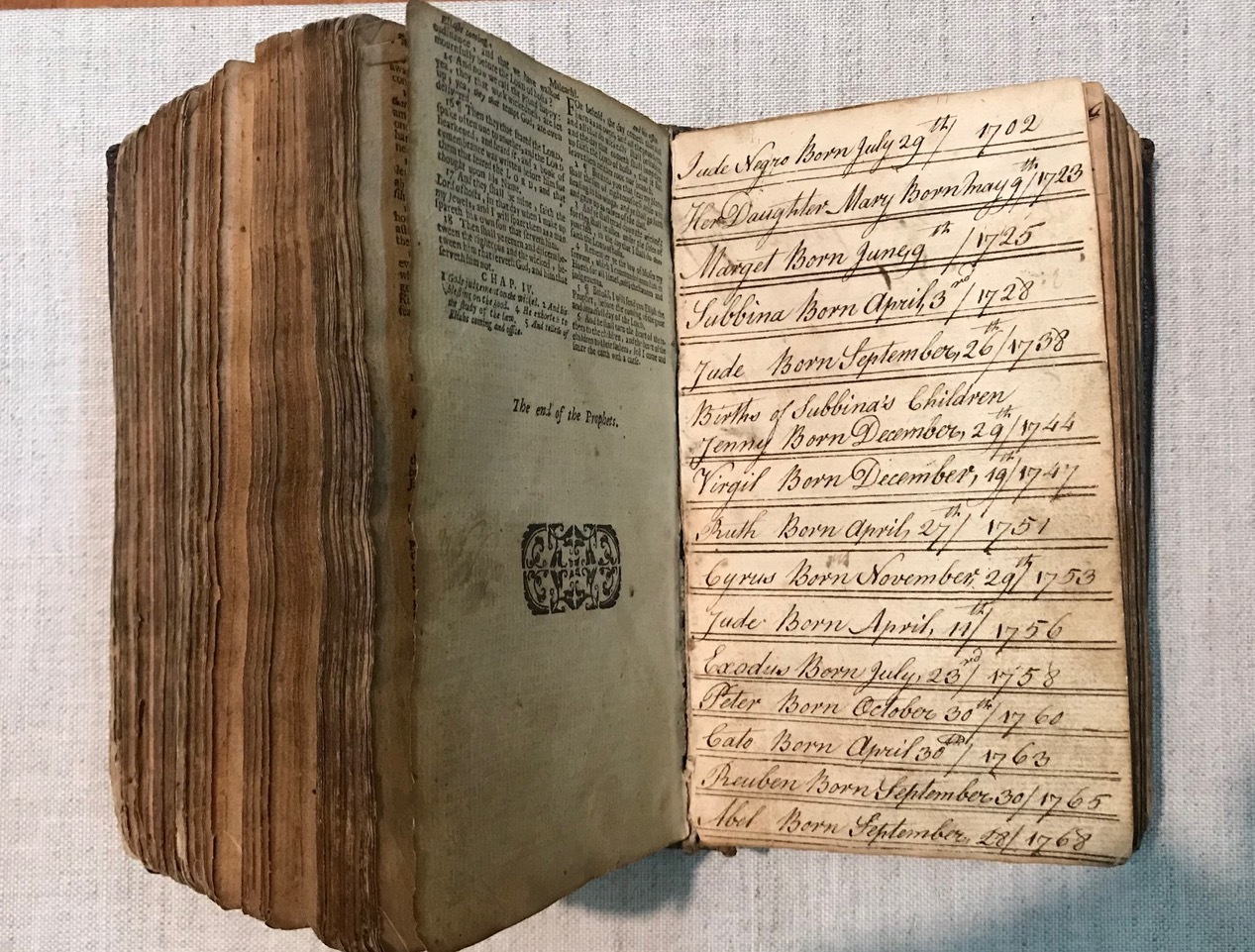

Greene first came upon Crook when she uncovered an old family Bible in the Hampton Library’s archives about 20 years ago. The Bible had been donated to the library sometime after the death of Crook’s granddaughter, Roxanna Rugg, in 1923. In it, family members recorded their genealogy, beginning with Crook’s grandmother, who was listed simply as June Negro and was born on July 9, 1702.

After learning of Crook’s letter, Greene tried unsuccessfully to trace the niece through the genealogy in the family Bible and is not even certain if she was on the Crook side of the family or his wife, Chloe’s, side.

Greene said it is not known if Smith responded to Crook’s letter. But a second letter, from Levi Hildreth, who was then the town overseer of the poor, informed Smith that his slave would potentially become a ward of the town, and that any expenses accrued on her behalf would be charged to him.

“This was all about money and the town not wanting to be charged with keeping her,” Greene said.