On board was the stench of regurgitated squid, rotting in the heat of the sun. There were cockroaches the size of mice and undrinkable water. Belowdecks was an airless, lightless hole where crew members suffered to sleep.

A whaler from the mid 1800s, as the industry had begun its slow decline, recalled the brutal conditions on the ships that navigated the oceans in pursuit of whales, disabusing the notion that whaling was ever a romantic adventure.

“Everything is drenched in oil. Shirts and trowsers are dripping with the loathsome stuff. The pores of the skin seem to be filled with it,” the unidentified seaman wrote in 1856. “You feel as though filth had struck into your blood, and suffused every vein in your body. From this smell and taste of blubber, raw, boiling and burning, there is no relief or place of refuge.”

And to clean up the mess? There was urine.

Still, it was better than the mental, physical and emotional abuses of slavery.

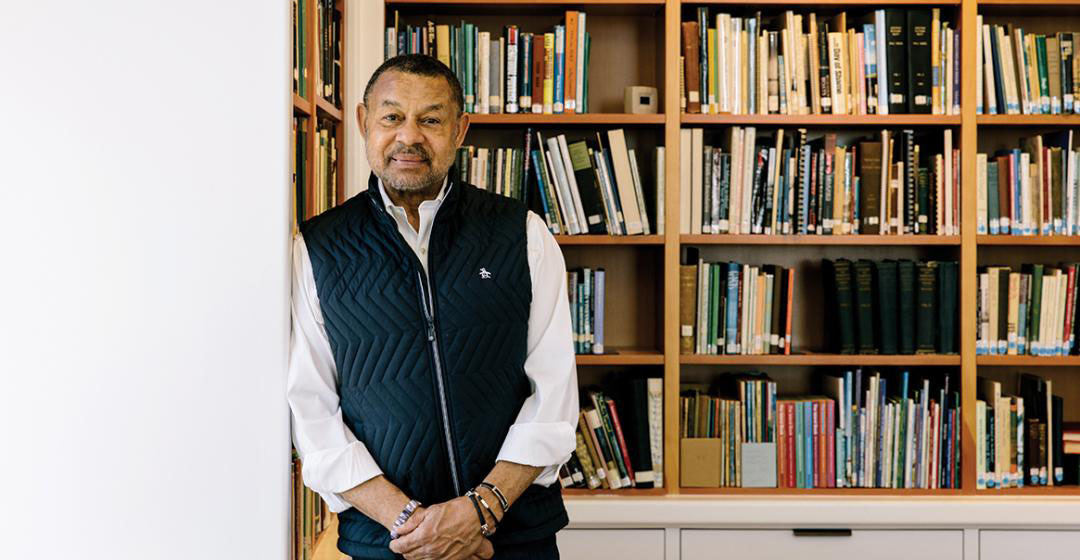

“They would use buckets of their own urine to clean their clothes,” said Skip Finley, author of “Whaling Captains of Color: America’s First Meritocracy.” The book is an exploration of the successes and struggles of Black people, Native Americans and Cape Verdeans and those of mixed races in the whaling industry, from the early 1700s to its end when the last whale ship returned to New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1928.

“The conditions were terrible, absolutely awful,” Mr. Finley said in an interview last week. He will speak about his book and the lives of whalers of color during a Zoom presentation hosted by the Southampton History Museum on Thursday, February 18.

But while whaling was a hideous occupation, it provided opportunities for Black men — free men and escaped slaves alike — at a time in American history when the threat of being returned to enslavement — or being enslaved — remained a real worry no matter where you were on land. And it was an industry where many men of color were able to rise through the ranks to become masters of their ships, with some even owning their own vessels.

In the decades and centuries prior to the Civil War, Black people were never truly away from the possibility of slavery. Laws like the Negro Seaman’s Acts and the Fugitive Slave Acts eliminated any true sense of freedom for most Black people, allowing slave owners to retrieve their property, especially those who may have escaped to the north, when slavery was finally outlawed.

“What is more,” writes Mr. Finley in the introduction to his book, “the law dictated that anyone Black — free or not — could be taken against his or her will on the strength of anyone white claiming to be that person’s owner, without basic due process rights like a jury trial.”

Through the centuries, colonies and states went through extraordinary measures to define and maintain Black people as slaves.

As far back as 1636, slavery was codified in New England’s early laws, which included not just Black people but Native Americans as well. Mr. Finley notes in his book that a British battle with the Pequots in 1637 resulted in many Pequot women and children being taken into slavery in the colonies, while the men were sold into slavery in the West Indies. In 1719, he writes, all slaves “not entirely” Indian would be counted as Black in South Carolina.

For many years in the South, slave owners exercised the concept of hypodescence, the notion that a person was considered Black with only the smallest amount of inherited Black blood. In 1662 Virginia, it was decided that “any child born to an enslaved woman would also be a slave, and any person with mixed blood who resulted from such a pairing would be assigned the race of the nonwhite parent,” Mr. Finley wrote. In 1705 the “blood fraction” laws established that anyone who was one-eighth Black could not be labeled as white.

The motivation for these laws, Mr. Finley points out, was economic. There was a big new world to build, and slaves offered an abundant supply of free labor with which to build it.

In the North during the whaling era, it would not be unusual for free Black people to work on a farm, or in local shops or at a trade. But even in the North, people of color were considered second class citizens by the white ruling class, despite their status as free men or being gainfully employed.

And as more escaped slaves made their way north, many of the routes they took led to port towns like New Bedford, Sag Harbor, Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket with a whaling industry and an entry into the comparatively safe open sea.

Life on land was threatening. On the water, though, whalers of color were treated as equals to the other crew on board, so there were good reasons for some to endure the brutal life on a whaleship.

“You could lead your life as a man, and not as someone’s possession,” Mr. Finley said last week.

And the window of opportunity remained open for many years. Of the estimated 175,000 crew who went to sea to catch whales during the roughly 200 years of the industry in America, about 95 percent of them only went once, said Mr. Finley.

“You’d have some blonde-haired, blue-eyed guy go out and get sick before they even got out into the ocean, and you know he wasn’t going to come back again,” Mr. Finley said with a laugh. There was an approximately 30 percent desertion rate among those in the trade, due in large part to the deplorable conditions, stultifying boredom and violent captains who regularly abused their crew.

About 30 to 40 percent of those onboard whaleships were people of color, Mr. Finley said, many who signed on for repeat tours; some single men who had no particular ties on land, and others who managed to eke out a living and support a small family at home.

And, importantly, people of color were accustomed to hard lives. Native Americans who had suffered at the hands of the Europeans who had cordoned them off into hardscrabble lives on reservations. Blacks who had been enslaved. And those who came on board from the Cape Verde Islands off the coast of Africa, a significant population of whalers who left a country that had suffered long periods of drought and famine.

And so there was a great attraction for Black people and other people of color to join the whale crews that dotted lower New England and Long Island, from Provincetown and Nantucket, Massachusetts, through Rhode Island and Connecticut, down to Sag Harbor, Greenport and Cold Spring Harbor in New York

What they found once they signed on was an environment that was dreadful, of course, but one that celebrated skill and performance above all, race be damned. In particular, Native Americans were respected for their skill, and it was said that hardly a whaleship left Sag Harbor without a Shinnecock crew member aboard. It was the Shinnecock, after all, who taught the early white settlers how to catch whales off the ocean beaches.

“There would have been no American drift-whaling fishery without Long Island’s Shinnecock tribe,” Mr. Finley writes. “The Shinnecock, said to have been the best harpooners, introduced European colonists to drift whaling.”

Mr. Finley notes that oppression had brought together Black people and Native Americans and many of the whalers who shipped out from the northeast’s great whaling ports were of mixed heritage, several of the captains mentioned in Mr. Finley’s book included. Paul Cuffee, who hailed from Martha’s Vineyard, was probably the first of the whalers of color to command a ship — one he actually owned — when he left the port of Dartmouth just south of New Bedford in 1778.

Interestingly, and disturbingly, white politicians actively encouraged the pairing of Black people and Native Americans, observed Mr. Finley, largely in an effort to dilute tribes’ identity and to weaken their hold on rights to land and government payments. For centuries, those efforts have been a struggle locally with both the Shinnecock and Montauket nations.

To underscore the efforts to undermine the Native Americans, Mr. Finley quotes U.S. Senator Anthony Higgins of Delaware in congressional testimony from 1895: “It seems to me one of the ways of getting rid of the Indian question is just this of intermarriage, and the gradual fading out of the Indian blood; the whole quality of and character of the aborigine disappears, they lose all of the traditions of the race; there is no longer any occasion to maintain the tribal relations, and there is then every reason why they shall go and take their place as white people do everywhere.”

While life onboard ship was not without its share of racism, there was a culture that rewarded excellence. It was, as the subtitle of Mr. Finley’s book says, a meritocracy. Last week, he told the story of a slave owner who hired his slave out to a trip on a Nantucket whaler. The man proved so good the ship’s captain offered to pay the slave directly to stay on, cutting out the owner.

“If you find yourself a couple hundred miles out to sea and something happens to the captain, you’re going to look to see who it is that’s going to get you home, or get you on to the whales,” said Mr. Finley. Often times it was a whaleman of color, someone who had the experience of returning to the trade time and again.

One of the things that made the environment level, at least from a racial standpoint, is that on small ships like the barks and brigs most often used in whaling, everyone had to get along and work together in order for there to be success. And, whaling being the dangerous career that it was, you had to be able to rely on your fellow shipmates.

One of the more successful whalers of color was Ferdinand Lee, a Shinnecock of mixed race who sailed out of Sag Harbor, as well as New Bedford and San Francisco, in a career that spanned two decades. Mr. Lee came from a family generation of whalers, including his four siblings. Mr. Lee and his brother, William Garrison Lee, are among the 52 whalers of color who became captains that Mr. Finley profiles in his book; but they are the only two identified who hailed from the South Fork. Mr. Finley is confident there were others, but a tremendous fire in Sag Harbor in 1845 destroyed much of the whaling industry’s records here.

The Lees’ father was James Lee, an escaped slave from Maryland who married Roxanna Bunn, a Shinnecock. The five Lee brothers, including Notley, James and Robert, together logged at least 25 whaling trips.

It appears that Ferdinand Lee began his whaling career on board the Young Phenix, a New Bedford whaleship sailing out of San Francisco in 1857. Mr. Lee was about 21 years old at the time, and in the log book for the voyage he is identified as Black from Southampton. He sailed on the Young Phenix again in 1860, and, in 1864 — again identified as Black — he achieved his first command as the third replacement master aboard the ship Roman.

Becoming a master while at sea was not all that unusual and was one of the routes taken by whalers of color to advance.

“Half of those who became captain did so because something happened to the original captain,” said Mr. Finley. “It could have been a customs agent who [made the appointment], or they could have been voted in by the crew: ‘You’re the guy.’”

Unquestionably, Ferdinand Lee was a skilled whaler. Once the small whaleboats were launched over the side and rowers pulled to chase a whale across the water, it was frequently the captain himself who stuck the beast with a harpoon. In the records Mr. Finley provides, Ferdinand Lee came up placing in the top 25 list of whales killed by captains of color. He was 23rd based on dollar value of his kill, $933,002 in today’s money, and 24th based on total whales killed, 16.

But while skill was one measure used to promote someone on a whaleship, an ability to manage and discipline a crew was another, and captains of color had to discipline white sailors as severely as any of the other crew. It was not uncommon that they would have put someone in shackles on board ship who they would not be able to look in the eye on dry land.

Ferdinand Lee was tested on several occasions, and during his tenure as master of the Callao, from July 1871 to September 1875, the log book indicates he put the cook in irons, and disciplined the first mate — who was a bully and abused the men under him — by discharging the man “for not getting along.” While first mate on the Eliza Adams he recorded “Thomas Coring [was] put in irons and hands tied above his head for using mutinous language and disobeying of orders.”

While it is hard to tell from the log books, racial tension on board may have had something to do with the results of his management style, but Mr. Finley acknowledges Mr. Lee lost most of his men through discharge or desertion.

Like his brother, William Garrison Lee also ascended as a replacement captain. He took command of the Abbie Bradford after its captain died on an 1880-81 voyage. He had a long career as a whaler, starting out as a green hand at age 16 aboard the Pioneer in 1854. His career was marked by a couple of highlights that resulted in near-death experiences. First, he was on board the Nassau when it was burned to the waterline by the Shenandoah shortly after the Civil War ended. Then, he was aboard the Rainbow in 1885 when it was crushed by ice in the north Pacific.

William survived and was transferred to the Amethyst, where his brother Ferdinand was serving as second mate. The ship had left San Francisco on February 21, 1885 headed for the North Pacific, where the whale fishery was being pushed further up into the Arctic.

A report from the Daily Alta, a San Francisco newspaper of the time, said in its December 15, 1885 edition: “Considerable anxiety is felt in shipping circles as to the fate of the whaling bark Amethyst. This vessel went north during the past season, but has not yet returned to this port. The Atlantic sighted her off Cape Lisbon on October 12th or 13th off the whaling ground and supposed to be on her way to this port. Some sixty days have elapsed since then, or thirty days more than are required to make an average passage from that point to this port … The Amethyst was commanded by Captain Cootey and sailed from here with a crew of thirty-six or thirty-eight men, Mr. Walker being the first officer and Mr. Lee the second. Some time ago she was reported by incoming vessels to have a catch of five whales. When she was seen by the Atlantic she was not near enough to be spoken. That some accident may have befallen her is generally supposed …”

Like many other whaleships, the Amethyst never returned to port and was declared lost in the Arctic. And the brothers Lee, two of the most successful whalers of color from the South Fork, assumed perished.

Skip Finley’s free Zoom talk on Thursday, February 18, will begin at 11 a.m. It is being presented by the Southampton Historical Museum and co-sponsored by the Rogers Memorial Library and the Southampton African American Museum. Register in advance at southamptonhistory.org.