La Amistad came ashore in Montauk at Culloden Point on August 26, 1839. Now, the site will be home to Montauk’s first New York State historic marker dedicated to the brave souls aboard the schooner.

A reflection and celebration presented by the Eastville Community Historical Society, the Southampton African American Museum and the Montauk Historical Society will be hosted at Culloden Point at 4 p.m. on Saturday, August 26. Additionally, a screening of the Steven Spielberg film “Amistad,” followed by a panel discussion on Sunday, August 27, will take place at the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor, from 1 to 3 p.m.

The captured men on the slave ship La Amistad came ashore in Montauk looking for fresh water, food and a way back to Africa. Instead, they were captured and seized, along with the ship, and towed to Connecticut, where they were locked in jail to stand trial for mutiny.

“As you stand there and look out to the water, it’s framed in beautiful greenery,” said Mia Certic, executive director of the Montauk Historical Society. “It looks as it did in 1839 — untouched, no view of houses.”

The Teçora, a Portuguese slave ship, left what is now Sierra Leone in 1839 with an estimated 500-600 captured slaves aboard. Many had been kidnapped and torn away from inland villages, their homes, their families, and sold into slavery in the port of Lomboko — an infamous slave factory in Africa. The conditions on the Teçora were inhumane. People shackled to each other by hands and feet, and forced into spaces so cramped people couldn’t stand or move. After eight weeks of being aboard the Tecora, where food and water were restricted, the slave ship finally landed in Cuba, where the men and children would be illegally sold into slavery.

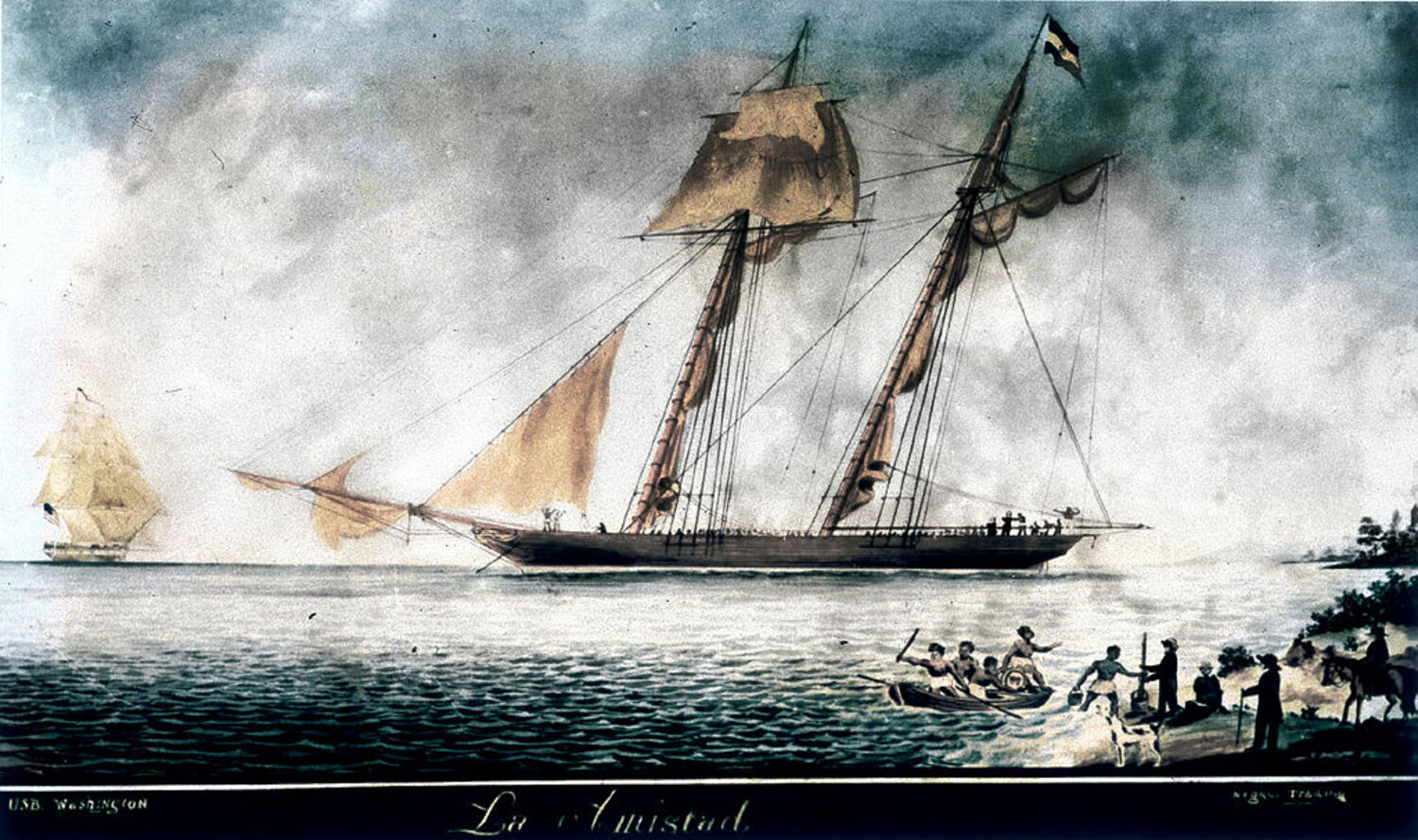

The kidnapped survivors were brought ashore at night, to avoid detection, because by that point, the slave trade had been made illegal. The African captives were put into holding cells outside Havana until they were auctioned off to an owner. After a few weeks, 49 of the men were purchased by a Spaniard named José Ruiz, who intended to sell them to sugar plantation owners in the center of the island. They joined four children, ages 7 to 12, who were purchased by another Spaniard, Pedro Montes, from a tobacconist in Havana. They were all loaded onto the Amistad, a compact, speedy schooner. The journey was expected to last three to seven days.

“They were put on the boat and had no idea where they were heading,” Cetric added. Aboard the ship, the men were taunted by the cook. Water and food were being withheld, the prisoners thought they would be killed. Together, the Africans agreed that they would rise up and take over the skeleton crew consisting of the captain, cook, two crew members, and a slave called Antonio, who belonged to Captain Ferrer. The other two men on the boat were Pedro Montes and José Ruiz, the enslavers.

The plan was to capture the ship and sail back to Africa. The story states that Joseph Cinque, the leader of the mutiny, found a nail and managed to use it to unshackle himself and his fellow prisoners. With no knowledge of sailing, the prisoners spared the lives of the two slave owners to have them sail the ship to Africa. Fearing for their lives, the two men agreed. At night, the Spaniards set their course to the northwest, hoping to be intercepted by an American vessel.

This went on for two months, until the Amistad found itself traveling along the south shore of Long Island. On August 26, 1839, the Amistad rounded Montauk Point and traveled another few miles to Culloden Point, to go ashore to hunt or try to find someone to barter with for supplies.

Henry Green and Pelatiah Fordham, ship captains from Sag Harbor, were hunting at the point. Using some sign language and a few English words, the Africans were assured that they had not landed in a slave country — New York was a free state by 1839. As the exhausted men aboard the Amistad stood on the shore negotiating, the U.S. brig Washington appeared nearby and boarded the Amistad fearing it to be a pirate ship. The officers, Thomas Gedney and Richard Meade, boarded the Amistad and were met by Ruiz and Montez, who told them their side of the story. La Amistad was seized and believing Gedney and Richard Meade were the rightful owners of the human cargo, towed the ship to Connecticut. At the time, New York wasn’t a slave state anymore, but Connecticut was. The boat was towed across the Block Island Sound to New London, Connecticut.

These men were not born into slavery, which Cetric explained was the key point of the court case.

“These people were kidnapped and put on a horrible slave ship with shackles and taken to Cuba,” Cetric explained. “This was illegal.”

The kidnapped men and children aboard La Amistad ended up spending over a year in prison awaiting trial. The trial, United States v. The Amistad grew national attention. The public fervor and abolitionist movement grew in favor of the captured and wrongfully accused. John Quincy Adams, a former U.S. president who was then a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, argued their case.

The case hinged on the fact that they had not been born into slavery, they’d been born free. This meant that they had the right to fight for their freedom and were, therefore not guilty of mutiny — they had the right to self-defense.

“It’s the story of triumph,” Cetric said. “We’re really looking forward to this. I think it’s great that it’s going to be Montauk’s first historic marker.”

Cinque was coined as the mutiny leader.

“He was this brave, powerful guy who seemed to be the one who put everything together. He was looked upon as the leader,” Cetric explained.

After the trail, most of the men went back to Africa. Some stayed in the United States, where they converted to Christianity and did missionary work.

“There’s so much Black history here,” Brenda Simmons, executive director of the Southampton African American Museum said. “So many people don’t know about it. It’s important for us now to tell our story.”

Simmons said the one quote that sticks out to her specifically from the La Amistad case is, “And the proof is the length to which a man, woman, or child will go to regain it, once taken. He will break loose his chains. He will decimate his enemies. He will try and try and try against all odds, against all prejudices, to get home.”

“The significance of the Amistad is so important to the region because many people believe it happened elsewhere, but it happened right here,” Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, the executive director of the Eastville Community Historical Society, said, adding that the Amistad weekend is meant to recognize and make sure people never forget the story.

“It’s going to be fantastic and spiritual,” Grier-Key said of the historic marker unveiling. “I am looking forward to it. We can’t erase this from our memories or from American history. We must commemorate and honor the legacy of the human spirit that survived.”

“Amistad is a tale of human courage,” Simmons added. “It’s something that people need to understand — the pain and the indignity that happened. These were free men. We really want to pay homage to this historic event. It’s very important.”

The historic marker unveiling will take place at 4 p.m. on Saturday, August 26. There will be reserved parking at Gosman’s big lot, with the Hamptons Hopper providing shuttle service to the event at Culloden Point. The parking area will be marked. The event is limited to 75 registrants. Reservations can be made on the Montauk Historical Society website, montaukhistoricalsociety.org.

Additionally, the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor will host a panel discussion about La Amistad, illustrated by scenes from Steven Spielberg’s landmark film, “Amistad,” on Sunday, August 27, from 1 to 3 p.m. The screening and forum will be moderated by Grier-Key.