When Tela Troge, Darlene Troge, Becky Genia, Donna Collins-Smith, Waban Tarrant and Danielle Hopson-Begun started Shinnecock Kelp in 2021, they were a small organization with big aspirations.

By embarking on an effort to own and operate their own kelp hatchery in Shinnecock Bay, the group, all members of the Shinnecock Nation, were seeking to restore the health and biodiversity of a body of water key to the tribe’s ability to survive and thrive, to create an avenue for economic growth and ingenuity for the nation, and to combat climate change, which poses a unique threat to the Shinnecock people.

Through hard work and the creation of several valuable partnerships, the women have done just that and in more recent months have been expanding their reach and influence.

Earlier this month, The Nature Conservancy announced that it would award $75,000 to Shinnecock Kelp Farmers, a nonprofit that has the distinction of being the first Indigenous-owned and -operated kelp hatchery and farming collective on the East Coast, to use toward expanding its operations.

The money was provided specifically from The Nature Conservancy in New York’s Common Ground Fund, which was established to catalyze and enable new and existing conservation work in New York that advances equity, justice and land sovereignty.

Expansion of the hatchery will allow the many benefits that kelp farming and harvesting offers to have an even greater impact.

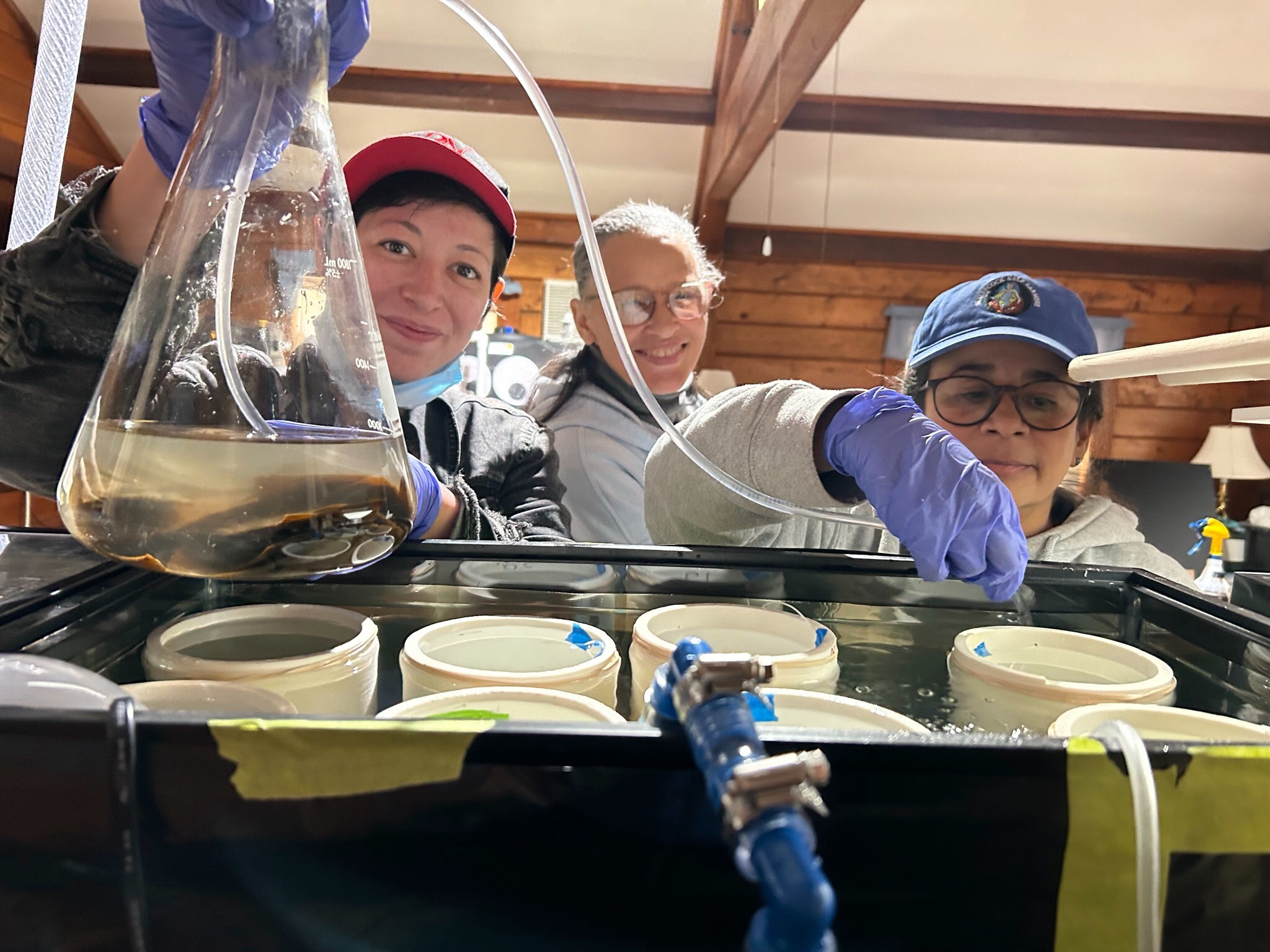

With the help of the Sisters of St. Joseph Villa in Hampton Bays — which donated space for the organization to build a hatchery, where kelp seeds are cultivated inside large water tanks before being transferred to Shinnecock Bay and Heady Creek — the farming operation got its start.

The kelp provides benefits both while it is in the water, promoting biodiversity as a habitat for shellfish and sea life, and naturally removing nitrogen from the water, and it’s also valuable when harvested, because it can be turned into a natural fertilizer.

Being able to sell the harvested kelp as a natural fertilizer, meanwhile, has two benefits as well: It reduces the amount of harmful chemicals entering the waterways from synthetic fertilizers used on nearby lawns and estates, and also provides a revenue stream for the Shinnecock Nation.

Kevin Munroe, the Long Island preserve director for The Nature Conservancy, said he’s thrilled to partner with the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers, and said the money comes with no strings attached. “They can use it for whatever they want to expand their kelp hatchery,” he said. “Whether that’s more materials, more staff, or even waders and boots.

“These are six incredible women trying to do amazing work, and we wanted to help them. They’re incredible innovators, they’re visionaries — we’re not trying to tell them what to do. We’re thrilled to be learning from them and partnering with them.”

Munroe, an East Quogue resident, said he first became aware of Shinnecock Kelp in summer 2021, when he met Hopson-Begun during outreach The Nature Conservancy was conducting to get a better sense of how people were using the organization’s more than 100 preserves spread throughout the state.

“We had a great conversation and she wanted to learn more about the preserves that border Shinnecock Bay,” he said. “We had shared goals and objectives, and we’re both interested in doing everything we can to help Shinnecock Bay be a healthier ecosystem.”

Partnering with Shinnecock Kelp is also in keeping with another priority for The Nature Conservancy. “We’ve been working hard around the world to support and partner with Indigenous people,” Munroe added. “Indigenous people have incredible wisdom and cultural knowledge about how to steward and take care of the land, so it makes sense for us to partner with them and learn from them.”

Tela Troge said she is excited about the partnership as well and spoke specifically about the sense of urgency related to increasing production and spreading the word about what they’re trying to do, and why it’s important not just for the Shinnecock people but for everyone.

“For years, it was projected that by 2050, our reservation would be underwater due to climate change induced sea level rise,” she said. “That timeline has since moved up to 2040. Urgent problems exist, and they can no longer be ignored.

“When we combine traditional ecological knowledge with cutting-edge science, we see leaps and bounds in what we can do,” she added. “We are grateful for this support and partnership with The Nature Conservancy. It’s a promising start for what needs to be done considering the time that we have to do it.”