At a late summer wedding in Amagansett, Lorraine Dusky met one of the loves of her life.

Perched on a couch next to her husband, Anthony Brandt, she took in the woman seated across from them — short in stature, big in personality — and they exchanged pleasantries and introductions.

When Dusky didn’t react to her name, her new acquaintance pointedly asked, “Do you know who I am?”

“I couldn’t place her, but I knew that she was somebody. I couldn’t pin it down — and I told her,” she recalled. “And she said, ‘If I were a man, you’d know who I was.’”

Dusky laughed softly at the memory. “I will tell you, in that moment, I felt like this woman and I were going to be friends,” she said.

Her name was Audrey Flack.

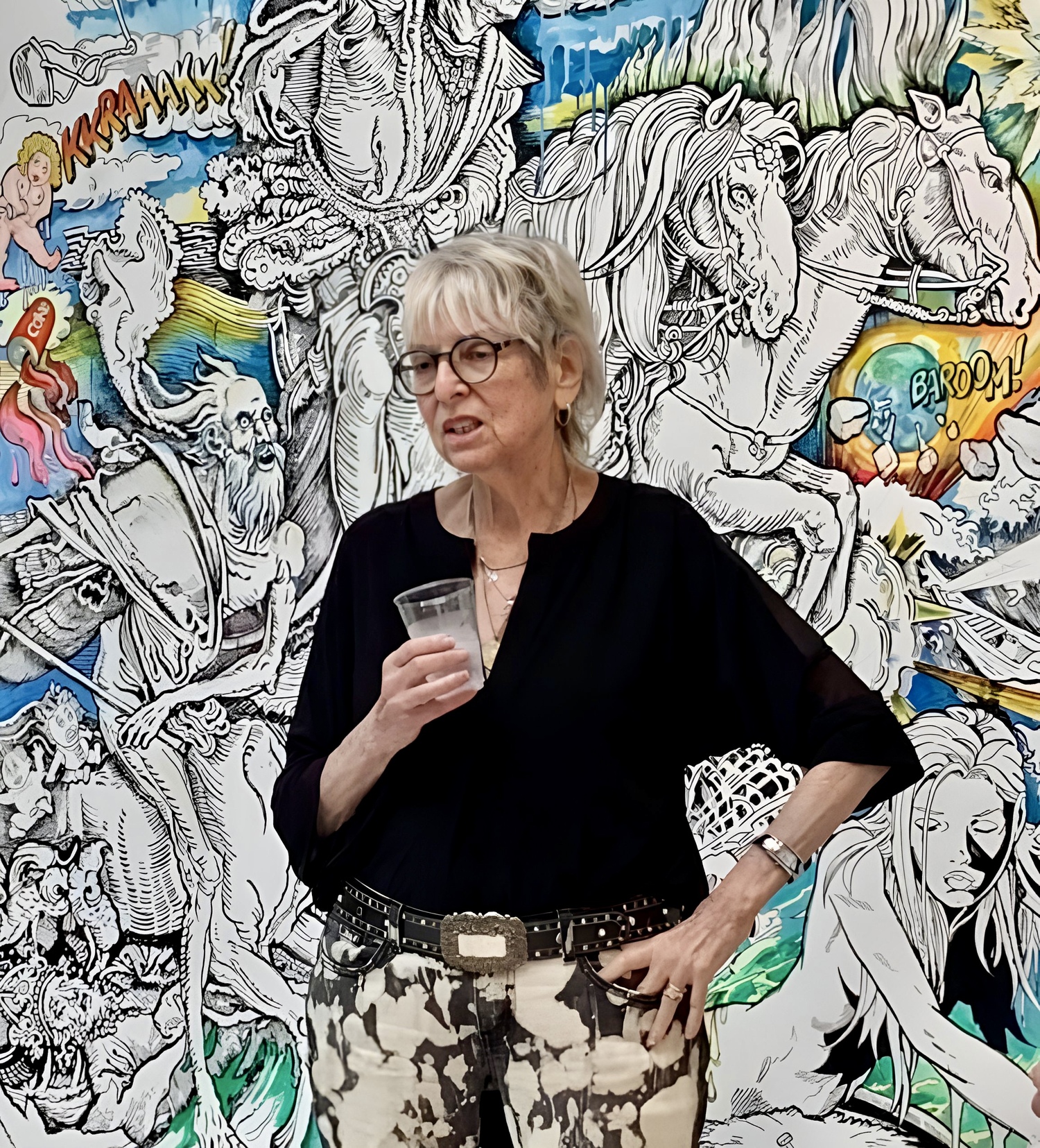

In the art world, she was a behemoth — a pioneer of photorealism whose career, which spanned seven decades, challenged the male-dominated, sexist landscape of the time. She was demanding, fierce, blunt and fearless, a force of nature in every space she occupied. Her brilliance shined.

But to those who knew the woman behind the public figure, Flack was curious, open, thoughtful and intimate. She was a feminist. She shared her strong opinions freely, and no subject was off limits. She was a wife, a mother and a confidante. She was a best friend.

Last Friday, June 28, Flack, who split her time between East Hampton and New York, died of a heart complication at Stony Brook Southampton Hospital. She was 93.

“You never think somebody’s going to leave, especially people like that in your life,” her longtime friend Amy Zerner said. “They’re always there.”

“And when you were with her, you were touching greatness,” Zerner’s husband, Monte Farber, added. “Life is very different without her being in it.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1931, Flack studied art at Cooper Union before painter Josef Alberts recruited her to attend the Yale School of Art on a scholarship. She immersed herself in the Abstract Expressionism movement, both as a style and a scene — socializing with the likes of Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, whose advances she rejected, at the legendary Cedar Tavern.

But she turned her back on the genre and its debauchery, according to longtime friend and gallerist Louis Meisel, and married in an effort to find stability. Her attempts were thwarted, though, and in 1968, she left what became an abusive relationship, even in the midst of raising their daughters, Hannah and Melissa, who is nonverbal and has autism — a diagnosis that came at a time when the condition was not understood.

Two years later, Flack married her high school sweetheart, Bob Marcus, and he adopted both of her girls. “They were devoted to each other,” Zerner said. “They loved each other, completely,” Farber said.

Motherhood led Flack to what would become photorealism, starting with snapping portraits of her children and painting them, Meisel said. She was the one female photorealist in a sea of men, whose tastes trended toward cars and trucks, lifeless streets and cold scenes, Dusky explained.

She was their antithesis.

“Her photorealism is full of lipsticks and crystal balls and mirrors and jewelry and cherries and cupcakes and Marilyn Monroe,” Dusky said. “Her photorealism is a whole different ballgame.”

In the early 1970s, Flack was painting still-lifes — not from life itself, but from her own photography. Assembling items of historic and symbolic significance, she created complex compositions, each item carefully arranged and styled, saturated with rich colors. By the end of 1985, her work was included in all four major art museums in New York City, including the Museum of Modern Art.

“She was a legend in our time and in the time before her, and the time before her and the time before,” explained Susan Meisel, a fellow artist and wife of Louis Meisel. “She would have been a legend in her time, no matter what time she was in.”

When their son, Ari, was born in 1982, Flack was in the middle of a creative block. She made a clay model of an angel, about 8 inches high, and gave it to him as a birthday present, Louis Meisel said.

“I said, ‘Audrey, this is clay. It’s not going to last. Can I get a cast?’” he recalled. “She said, ‘Do whatever you want.’ So I cast it in bronze and, a few months later, she came in and saw it. She said, ‘Oh, I think I’m going to become a sculptor.’”

For the next three decades, she devoted herself to the medium, creating figures of powerful women and goddesses, drawing from mythology and Egyptian iconography. She won competitions and made major public sculptures for numerous cities across the United States, including Rock Hill, South Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee.

Around 2005, she switched gears again and started attending banjo camp — and even founded a group, aptly titled Audrey Flack and the History of Art Band. Their repertoire: songs about a wide range of artists and art-related topics, set to bluegrass melodies.

But in recent years, Flack returned to the canvas for what she called her “Post-Pop Baroque” period — a departure from photorealism, yet still exploring themes of female empowerment, sprinkled with religious, pop and political references.

Come October, her final group of paintings will be on view in “Audrey Flack NOW” at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill.

“She’ll be missed, hugely,” her former studio manager, Severin Delfs, said. “She had such a big presence in so many people’s lives. It’s going to be difficult for a great many people. She had an impact on her close friends, on people who admired her art, on people who studied her. It’s really going to reverberate on so many different levels.”

Of the 50 major photorealist paintings that Flack created, 32 are in museums to this day, Meisel said. She has had dozens of solo exhibitions and participated in hundreds of group shows, domestically and abroad. Her work is housed in the collections of numerous museum collections, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he said.

And she was the first female artist, along with Mary Cassatt, to be recognized in an updated version of H.W. Janson’s iconic textbook, “History of Art.”

“She understood that art doesn’t happen because you think about it,” Dusky said. “It happens because you do the work.”

Flack encouraged those around her to chase their own ambitions — whether professional, personal, or otherwise. Within a year or two of working with her, Delfs found himself running just about every big life decision by her.

“She was combative and just cut straight to the wick. You could have a relationship with her like with nobody else” he said, “She just presented herself fully to everyone and said, ‘Either we get along, or we don’t.’ Some people are, like, ‘I can’t stand her,’ and some people are, like, ‘She’s the most amazing person in the entire world’ — and she was both of those things. She really was.”

Despite their 65-year age gap, the pair became great friends. She was like a grandmother to him, he said, and he was a member of her family. In addition to her two daughters, Flack is survived by two children, Leslie and Mitchell Marcus; four grandchildren, Debra and Rachel Marcus, and Zoe and Jake Diamond; and two great-grandchildren, Leon and Ethan Marcus-Pittman.

She was predeceased by a daughter, Aileen Marcus; and her husband, who died on May 10 at age 95.

“I think it’s one of the reasons she left,” Zerner said. “You know how soulmates go, one after the other.”

Last Thursday, according to Flack’s health aide, the artist had “a really good day,” Farber said. It started, as it often did, with an early-morning phone call from Dusky. Over the years, their conversations ran the gamut, from chatting about their lives, fashion and their aches and pains, to politics, relationships and, of course, art.

But that day, growing older was on Flack’s mind, Dusky recalled.

“I said something about how I’d probably go back to Detroit if my husband died and she said, ‘Oh, no, you can’t leave me,’” she recalled. “And I said, ‘You’re going to be leaving me,’ and she agreed.”

Before hanging up, they also talked about a cocktail party that they planned to attend together on Saturday night.

“The next morning, what I thought about immediately was if she had been there, we would be on the phone rehashing the party,” Dusky said.

When she got the news on Thursday night that her Flack was in the emergency room, Dusky rushed to the hospital. She arrived just in time, stealing a moment of consciousness to see her friend one last time.

“I told her that I loved her and she told me, ‘I love you,’ and we said goodbye,” she said, her voice hitching. “I’m so grateful for that.”