What if the stately manse under construction on a Southampton Town street wasn’t a second, or third, home for a 1-percenter? What if the elegant building actually accommodated affordable apartments for four families?

What if that “zombie house” in the neighborhood could be purchased and transformed into a home for a young professional couple?

What if a community of a half dozen cottages for single residents could be developed — or if the town provided no-interest loans to build accessory apartments in private houses?

Those and other methods for chipping away at Southampton Town’s seemingly insurmountable affordable housing crisis were discussed on Friday, May 20, as members of the Town Board presided over the debut of their Community Housing Fund plan.

Crafting a plan is a requisite in the move toward adoption of the CHF in November. Funded by a 0.5 percent transfer tax added to the existing 2 percent tax that generates revenue for the Community Preservation Fund, the proposed creation of the CHF is expected to be put before voters in November. It’s available to all five towns that already have a CPF to collect revenue for the acquisition of open space, historic properties and farmland, and for water protection: Southold, Riverhead, Shelter Island, East Hampton and Southampton towns.

Presented by Housing Director Kara Bak, the town’s CHF plan lays out an array of remedies, none of which is an all-purpose solution to a housing crisis that’s worsened in the last decade, and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under the CHF legislation, the money — Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman said it could be as much as $10 million per year — may be used for a variety of programs.

First-time homebuyer assistance is the primary focus of the plan, allowing the town to use CHF revenue to provide low- or no-interest loans to first-time homebuyers. It could help a homebuyer who qualifies to purchase a home but can’t save up the more than $100,000 needed for a down payment, Bak pointed out. The loan from the town would be paid back once the house is sold.

In a shared equity scenario, residents or employees of the town could split the cost of the home with the town. The low-interest or no-interest loan wouldn’t have to be paid back to the town while the recipient lives there — it’s repaid in full when the house is sold.

Acknowledging the homebuyer assistance program as the focal point, Councilman Rick Martel said he also likes the idea of a multifaceted approach.

Schneiderman noted the method doesn’t offer as much bang for the buck as developments that produce more units, or meet more needs, like employee housing or buying land and creating community housing units, two additional components of the plan.

Under the legislation, the town can give employers low-interest loans to create affordable rental units for workers. Participants in that program would have to obtain a rental permit and provide proof the place is being rented to employees.

The need for employee housing spans both the seasonal industries as well as local essential industries like medical and educational. Councilman Tommy John Schiavoni said he’s interested in exploring the concept of mixed uses with housing created over businesses in some areas. Schneiderman said he’d spoken with a constituent who wanted to create staff housing in an accessory structure on his land, but the zoning code prohibits it. That may be worth reviewing, the lawmaker said.

With an eye toward crafting more units, the CHF legislation allows the town to offer low-interest loans with flexible terms in conjunction with public/private partnerships looking to buy land and develop affordable units. The developer would then have to agree to keep the properties affordable.

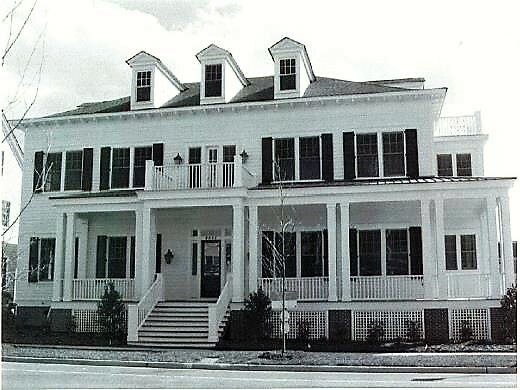

The supervisor seemed to favor the manor house idea, and seemed enthusiastic about the idea of a cottage community of smaller houses, “like an artists’ colony,” he said. Bak displayed a photo of a manor house that looked similar to a classic Hamptons mansion but actually accommodates four two-bedroom apartments.

It could be a creative way to fulfill needs for lower-income and younger residents, while retaining the characteristic look and feel of a local neighborhood. Schneiderman pointed out that under current zoning, a huge eight-bedroom house is permitted, but turning that same size building into four two-bedroom units is prohibited

Similarly, the supervisor reasoned that a cluster of cottages might ultimately have no greater septic need than one eight-bedroom abode.

The CHF may be used also, Bak informed, for the rehabilitation or purchase of existing houses. The plan notes the town could rehab buildings into affordable units for sale or rent to eligible residents.

It could also provide financial assistance to homeowners who are looking to build affordable accessory apartments in their homes. Proof of a tenant’s income and the rent would be required.

Housing counseling services could also help struggling homeowners find a way to avoid foreclosure and keep their houses.

“This is great — it’s a lot of information,” Councilwoman Cynthia McNamara offered. “I feel like we need to take each hamlet, hamlet by hamlet, and say, ‘This is the land that’s available.”

Before the town continues to buy and preserve land, officials need to look at what’s available. “We need a serious plan, I can’t stress that enough,” she repeated.

“You need to have the courage to rezone certain areas and say, this is a sustainable growth area,” Janice Scherer, the town’s planning and development administrator countered.

Schiavoni said it would be useful for the community to have a clear understanding of where the town has already created affordable housing projects. Speaking of the plan, he noted, “A lot of what we put in here is going to be on top of what already exists.”

Scherer said housing opportunities do need to be looked at in the context of specific hamlets. “It comes down to where you are,” she said.

And while creative ideas in the draft plan may have been cause for optimism, the existing outlook offered by VHB Engineering, the firm hired to define the town’s housing needs for the plan, was grim.

“The pandemic has only increased demand for housing in our area,” Bak affirmed, “driving up costs even further.”

Cost has rendered single-family homes beyond the reach of most local moderate- and middle-income families. On top of that, only 22 percent of properties in Southampton are rentals.

The housing director explained that a household is considered “cost burdened” when more than 30 percent of its income goes toward housing. While the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development considers $1,695 a month fair market value for a one-bedroom apartment in the area, demand has driven rental costs far beyond HUD standards. That means some 55 percent of renters in Southampton Town are “cost burdened.” Statewide, the figure is lower, at 44 percent. Twenty-two percent of the cost burdened households in Southampton meet the criteria for “severely cost burdened.”

And for those hoping to buy? The median home value — listed at $1.4 million — is more than triple national and state numbers. The high cost of rent, Bak said, makes it nearly impossible for a young family to save the money it needs for a down payment. Entry-level or starter homes are in short supply, also.

Looking at the town’s demographics, VHB determined the population of people ages 20 to 44 has steadily declined, while 20 percent of the town’s residents are 65 years old or older, with that number expected to increase rapidly. The aging population will need a mix of housing options, the plan states, from accessory apartments to assisted living facilities.

Younger people exiting the area can mean a dearth of volunteers for emergency services, as well as a lack of talented professionals serving in industries like medicine, education, and law enforcement. Schiavoni observed that once people have a secure living situation in a community, they are more likely to volunteer.

Consultants also learned that almost 29 percent of Southampton Town residents live alone, while 70 percent of the town’s housing stock has at least three bedrooms. Smaller housing types should be explored. Schneiderman reasoned that if older residents are living in two- or three-bedroom houses, renovating them to create accessory apartments “seems like a no-brainer.”

The VHB assessment also spoke of transit-oriented development — housing options near transportation hubs. The Speonk Commons affordable apartment development near the hamlet’s railroad station was cited as an example, but McNamara said that while she likes the TOD idea, she feels Southampton Town is always going to be a vehicle-driven community.

With more than 80 percent of housing units in Southampton being single-family, detached homes, the projects that introduce smaller and middle market housing, with more rental units are recommended in the study.

Outlining obstacles to the creation of affordable housing — beyond the high cost — the plan lists several constraints, existing zoning strictures among them. To allow the aforementioned manor houses or artists colony and even certain accessory apartments, the town’s zoning code would have to be revised. Scherer noted that changes could be made to allow more affordable developments whether the CHF passes or not.

Most of the barriers relate to the town code, she pointed out. Infrastructure and environmental constraints, as well as potential impacts to school districts could also be obstacles, the plan notes.

With the median home value in Southampton topping $653,000, triple the national average, who could qualify for assistance?

Area family median income eligibility figures recently released by HUD list incomes that could qualify for assistance. HUD sets income limits that determine eligibility for assisted housing programs including the Public Housing, Section 8 project-based, Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher, Section 202 housing for the elderly, and Section 811 housing for persons with disabilities programs. HUD develops income limits based on median family income estimates and fair market rent in specific areas.

A single person earning $50,900 makes 50 percent of the area median income, with a family of five at $78,500, according to the chart Bak displayed. Those are the low thresholds. Assistance could be available to people making as much as 120 percent of the AMI — that’s $123,000 for a single person, and $189,750 for the family of five. Again, a threshold of affordability is a household paying no more than 30 percent of income toward housing.

Median income lists at $89,199, while the median for renter households is $49,505. That’s another factor in the housing affordability gap.

Schneiderman recalled that when he was the supervisor of East Hampton Town from 2000 to 2003, he didn’t make enough money to qualify for down payment assistance. Neither did the mayor of Sag Harbor or Southold Town supervisor, he noted. Three community leaders who couldn’t afford homes in their own communities, was his point.

Speaking of expense, if it’s adopted, what will the CHF cost purchasers? Similar to the CPF, first-time homebuyers are exempt from paying the transfer tax. The legislation also raises the current CPF exemption threshold from $250,000 to $400,000, so those households buying a home for less than $1 million actually pay a lower fee.

In order for the proposed CHF legislation to make it onto November’s ballot, officials must adopt their housing plan, along with a town code amendment establishing the fund. Southampton Town Board members will host hearings on the two measures on June 14 and 28.

The ballot proposal must be sent off to the Suffolk County Board of Elections by August 8 and voters go to the polls on November 8.

If the proposal is authorized by referendum, the fund will become operational in January 2023, with the transfer fee imposed in April 2023.