State officials have remained mum about who has authority over the Shinnecock Indian Nation’s construction site along Sunrise Highway in Hampton Bays, leaving local officials pacing the floor and making it more likely that the Nation’s proposed electronic billboards will go up without any state resistance.

The state attorney general’s office and the State Department of Transportation are the two agencies that have been reviewing the matter, and they have yet to make a determination on the project—which, according to a report, could accrue more than $78 million in advertising revenue over the life of a 25-year contract, to be split by the tribe and the company installing the signs.

State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr., State Senator Kenneth P. LaValle and officials from Southampton Town all are waiting for a response from the state agencies to find out what, if anything, can be done to halt the project, as they are unsure who has the authority to make a decision.

A spokesperson for the DOT confirmed Wednesday morning that the matter is still being reviewed.

Meanwhile, town officials are scrambling to determine how best to respond to the Nation’s plan for a pair of 61-foot-tall electronic billboards along Sunrise Highway, on tribe-owned land, even as the work continues.

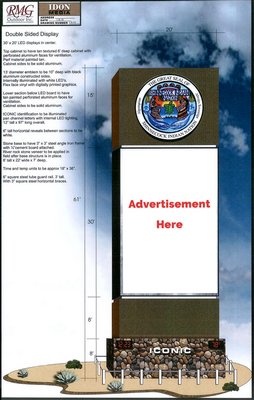

Concrete posts and footers have been installed for two 61-foot-tall, 20-foot-wide billboards—described by tribal officials as “monuments”—on the north and south sides of Sunrise Highway. Each will have a 30-foot-high LED digital display—on both sides of each billboard—for advertisements, with the Shinnecock Nation seal above that.

Contractors had begun installing some of the framework this past week, with the tribe maintaining that the work is on tribe-owned land, known as Westwoods, and not subject to local or state restrictions.

“There’s a sense of growing frustration,” Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman said Tuesday. “What do we do? Who’s going to help us? How do we stop this from happening? We don’t have a lot of good answers.”

A copy of a February feasibility study prepared by Idon Media LLC, the company the tribe is partnering with on the electronic billboards, provided by a confidential source in the Nation, and obtained by The Press, shows that the billboards will be double-sided and will cost about $3.5 million to install. Idon Media will cover all costs of installation, according to the 10-page report by the firm Johnsen, Fretty and Company, a financial adviser retained by Idon Media.

The tribe will split the advertising revenue from the billboards with the company, with Idon Media keeping 51 percent. In the first year, the report projects total revenues of $4.6 million, which means about $2.3 million for the tribe. That amount is projected to rise to $6 million total by the fifth year of operation, and over the 25-year contract period, the projected total income tops $78 million, to be split by the tribe and Idon Media.

“Management’s goal is to construct these one-of-a-kind, state-of-the-art digital monument signs to maximize advertising sales on each location,” the report notes, with emphasis added to “maximize advertising sales.”

Tribal Council Chairman Bryan Polite and Trustee Lance Gumbs both said that the report was inaccurate and did not come from the Nation. They did not provide any other details.

“I know what packet you’re speaking of, and if it does not come from the tribal government officially, then it’s inaccurate information,” Mr. Polite said.

Idon Media and its affiliate, Digital Outdoor Advertising, operate similar units throughout the country and focus on Fortune 500 companies as advertisers, listing Disney, fast-food chains, Sony Pictures and 20th Century Fox, Walmart, insurance companies, automobile manufacturers, and alcohol products among its clients.

On Friday, Mr. Schneiderman said he considered organizing a public rally to demonstrate opposition to the tribe’s plans for the billboards, but he later heard that local civic groups may be interested in holding their own rallies. He spoke with the Hampton Bays Beautification Association—one of the groups that expressed interest—at their meeting on Monday evening to explain the situation.

“If there is a rally, I may attend. But I know the civics are talking about it,” he said Saturday. “My phone has been ringing off the hook with people who are upset about the billboards. The more they find out about it, the more upset they are.”

The town is planning to get help in sorting through the legal dispute at the heart of the project. At a special meeting on Tuesday, the Town Board authorized Town Attorney James Burke to seek outside counsel, likely someone with a background in federal law as it pertains to Native American tribes, Mr. Schneiderman said.

“The signs are clearly out of character with the area and, in my mind, distasteful,” the town supervisor said, noting that he could support some other economic development ideas the tribe’s leaders have suggested—just not this one.

Town officials issued a stop work order for the project on Friday, April 26, and has made other attempts to ask the Nation to stop construction. Tribe members had submitted plans to the DOT instead of the town, because the state holds an easement along Sunrise Highway. The Nation maintains that Town Hall has no bearing on the project, since it is located on land, Westwoods, that tribal officials believe is sovereign land. The property straddles Sunrise Highway.

The Westwoods property has been the source of an extended legal battle once already—one that was unresolved.

A federal court found that the property was not sovereign land, though it is owned by the Nation. That decision was dismissed on appeal, though, based on the fact that the court decided it was not a federal court matter but a state court issue, since the tribe had not yet been officially recognized by the federal government. Recognition came following that appeal—but the matter was never re-litigated in either state or federal court.

Thus, the question remains: Who has jurisdiction over the site?

The tribe clearly owns the land, and the state has a right-of-way for Sunrise Highway. Because Sunrise Highway is part of the federal highway system, it is subject to its rules, which must be enforced by the state. Whether or not the state, or the town, has any ability to stop the project could be a matter to be decided in court.

It is possible that it will be up to the State Department of Transportation to try to shut down the project, though it so far has taken no steps to do so.

But tribe members do not consider this a topic of dispute—they are firm in their belief that they are authorized to erect the billboards and collect the revenue they will generate.

The Nation’s Westwoods property—on which the tribe had talked of building a gaming facility in the past, resulting in the federal court battle—stretches from Peconic Bay down to a narrow strip along Sunrise Highway between exits 65S and 66 in Hampton Bays. However, it is not part of the reservation.

In a layered history of voided legal judgments, it is a property that has passed between owners over time, which is at the heart of the court’s ruling that it is not sovereign land. Tribal officials have said in the past that the land was stolen from the tribe in the 19th century through the courts, then later re-acquired.

Mr. Schneiderman said he has been actively communicating with Tribal Council members, primarily Mr. Polite and Mr. Gumbs. He said—and Mr. Gumbs confirmed—that they have expressed some willingness recently to work with the town to lower the brightness of the display screen at night to limit its impact on nearby homes.

The town supervisor explained that the tribe originally planned to keep the brightness of 5,500 nits—a unit of measurement for luminance—which is typical for an outdoor LED display. But after some discussion, they agreed Wednesday to lower the brightness to 300 nits, about as bright as a laptop screen, at an undetermined point late at night, Mr. Schneiderman said.

Southampton has long opposed billboards within its borders, ever since it passed a law prohibiting them in the late 1970s. The ban was even upheld in several court battles shortly thereafter.

Mr. Thiele was the Southampton Town attorney when those trials took place in the early 1980s, and said he has opposed billboards on local highways since then.

“I’m in favor of the beautification of our highways, and I don’t see signs in that regard,” the assemblyman said. “But, on the other hand, I certainly would like to help the Shinnecocks with economic development. I guess I think that there may be better ways.”