In 1973, Chris Holden was in her first year as a physical education teacher at the Ichabod Crane Central School District in the Albany area, when she was presented with a particularly frustrating dilemma.

She was coaching the girls basketball team in a home game, and during halftime, she was approached by the school’s assistant principal, who abruptly informed her that they needed to stop the game.

“We were winning, and I said, ‘What do you mean?’” Holden said, telling the story last month. “And he said, ‘Well, we have a big boys basketball game tonight and people are starting to line up outside to get in.’ So I said, ‘Great, let them in, we’d love to have a crowd.’ And he said, ‘Oh no, we can’t do that.’”

As a first-year teacher coaching a girls team, there was a limit to how much Holden felt she could push back against her higher-ranking colleague — who also happened to be the coach of the boys basketball team. They reached a compromise, letting the clock run during breaks in the action and timeouts, so the game would end faster.

Holden went on to become a physical education teacher and coach at Southampton High School, most notably turning the Mariners field hockey program into a powerhouse and leading them to the state championship in 1999. She retired from teaching in 2004, but 50 years removed from that experience, the passion in her voice is still clear when she retells the story, and remembers how she felt in that moment, when her team of female athletes was expected to step aside, without complaint, to accommodate the boys team. Stifling her anger in that moment was a challenge, Holden admitted.

“I was rippin’,” she said. “But I was a brand new teacher in a new school. I thought, how much noise can I make and still keep my job?”

It’s preposterous to imagine something like that happening in today’s world.

In fact, it would be in direct violation of federal law.

Gender-based discrimination in education officially became illegal exactly 50 years ago, when former President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law on June 23, 1972. The statute was an amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and stated that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

The law applied to education broadly speaking, without any specific references to athletic programs, but its biggest legacy over the last half-century has been the way it has drastically changed the landscape for women and young girls when it comes to participation in competitive sports.

A world in which the U.S. women’s national soccer team can win a fight for pay equal to that of their male counterparts, and where professional women’s sports leagues like the WNBA can be created and thrive would not exist without Title IX.

In 1972, the year the law went into effect, girls comprised just 7 percent of all high school athletes in the country, with just 294,015 high school age girls competing on a team. In the 2018/19 school year (the last year numbers were compiled), female athletes comprised 43 percent of high school athletes, with 3,402,733 teenage girls participating on a high school sports team nationwide.

The percentage of women competing on college teams saw a similar sharp rise in the years following Title IX’s inception, going from 15 percent in 1972 to 44 percent in 2021.

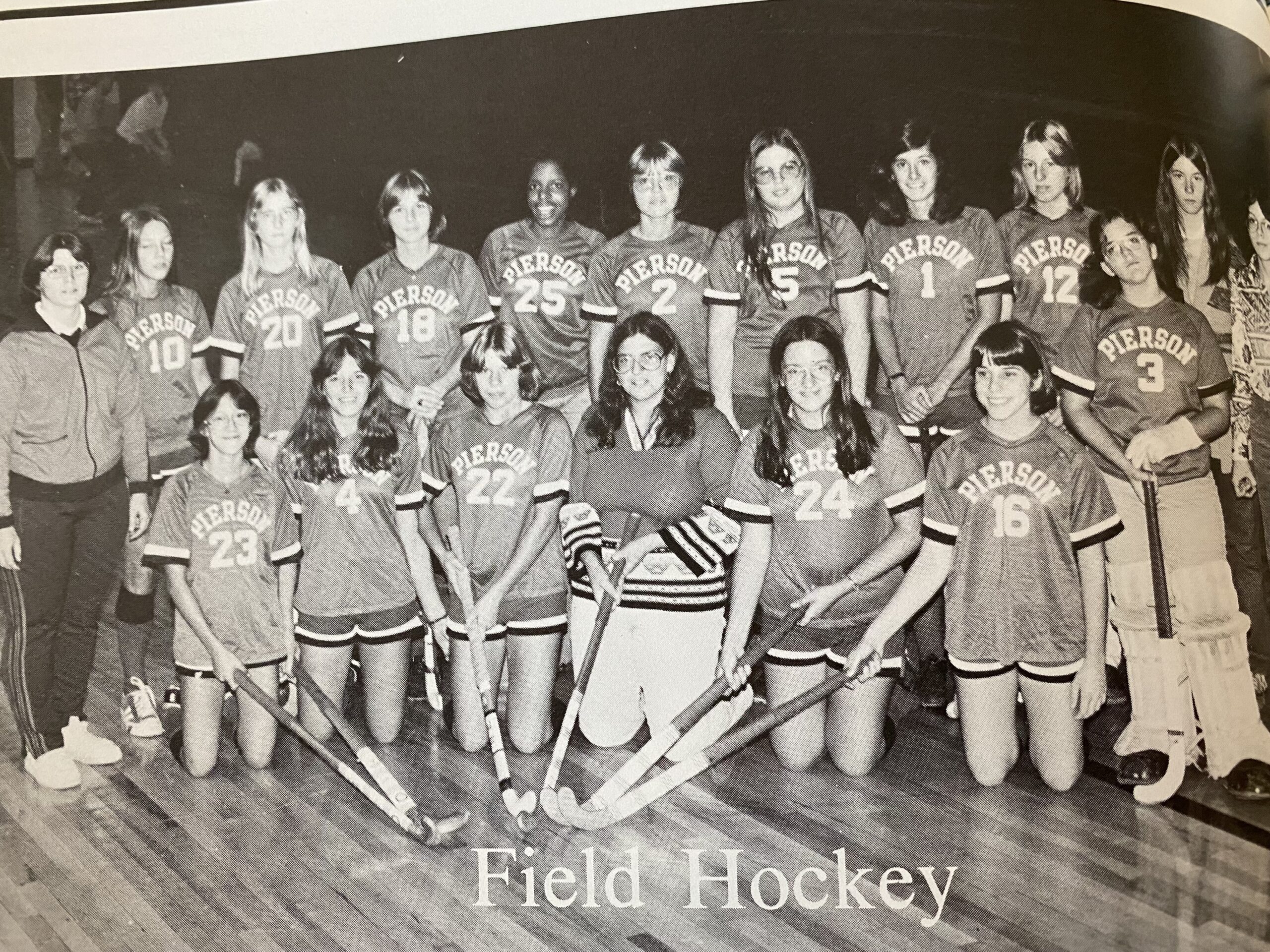

Those kinds of numbers would have been hard to imagine, and perhaps even unfathomable, for women like Holden, who were high school students in the years before the law was passed. Holden and her peers, like former Pierson High School phys ed teacher and coach Debbie Jayne, came of age during a time when the expectations for how young women should engage with sports were decidedly different than they were for young men.

“Back then, for girls, you had maybe four games in a season, and a sports day where the teams would come together and you’d play two or three games and have a picnic all together afterward,” Jayne said. She recalled how, during her time as a student at Port Jefferson High School, her brother had a much different experience.

“My brother played basketball, and they were county champions one year, and they had a full season, and they had their sponsors with cardboard schedules handed out to the businesses.”

Jayne and her other siblings and parents would attend her brother’s basketball games–always scheduled for the evenings–while attendance at girls games was sparse to nonexistent, scheduled at times when many parents couldn’t attend even if they wanted to, because they were still at work.

The rules in certain sports were tailored by gender as well. In basketball, girls played six-on-six, with two forwards and two defenders who were not permitted to cross the halfcourt line, and a pair of “rovers” who were allowed the full run of the court.

“They didn’t expect girls to be able to physically sustain going up and down the court,” Jayne said, adding that there was also a rule that an individual player couldn’t dribble more than three times consecutively. It was a stark contrast, she said, from the way she grew up in their neighborhood, playing alongside — and keeping up with — her brother and other neighborhood kids in a variety of sports, where there were never different rules for girls.

Boys teams weren’t only the recipients of more attention and more time spent on the court and on the field. They also had better resources. Both Jayne and Holden recalled that female athletes were issued a one sports “tunic” that they were expected to use for every sport they played, whether it was field hockey, basketball or softball, while the school provided different uniforms for boys teams for every sport.

Even when girls were encouraged to play sports, there was a marked difference in the mentality of how they were supposed to engage in those sports, often with an emphasis on participation rather than excellence.

“We were expected to get together after games with our opponents for cookies and punch,” Holden recalled, with disdain. “You learned that that’s what the culture was when it came to how girls were supposed to behave.”

Women like Holden and Jayne have the unique perspective of being able to compare what life was like for female athletes before Title IX, and how things changed after its creation, for the young women under their charge as coaches. Women who were playing high school and collegiate sports in the 1980s had their own unique perspective when it comes to Title IX. Julie Mullen is one of those women, and considers herself part of a “gap generation,” one that had started to see some benefits from Title IX even though the law was still in its infancy and limited in its scope.

Mullen graduated from Southampton High School in 1983, playing field hockey for Holden before going on to play field hockey at Fairleigh Dickinson University. She pointed out that while her generation “reaped some benefits” in terms of increased participation in sports because of Title IX, the law was also under constant attack, and several loopholes — like one during the Reagan administration that said that programs that did not directly receive federal aid didn’t have to comply — blunted the law’s effectiveness.

“There was definitely some backsliding,” Muller said. She recalled playing in the NCAA tournament in the mid-1980s. Her team was sent down on a bus to a game, and bused back to campus after the game, while boys teams were put up in hotels.

There was plenty of pushback against Title IX in the years following its inception, through the 1980s and even into the early 1990s. At the collegiate level, in order to meet compliance requirements, schools would often cut lower-tier men’s programs like swimming or wrestling, which led to a false narrative that providing more opportunities for women could only come at the expense of taking opportunities away from male athletes.

“For a while, the messaging was that Title IX was going to lead to cuts in men’s programs, but when you look at the reality, some sports were negatively impacted by decisions that were made, but those decisions were not based on Title IX but instead administrations were making the decision to put more money into the revenue sports like basketball and football and undercutting men’s Olympic sports,” Muller explained.

Title IX essentially exposed the fact that many colleges and universities dedicated the bulk of their resources and funding to a small handful of teams — typically those revenue-producing sports of football and men’s basketball.

As a collegiate athlete in the 1980s, Muller had a front row seat to experiencing the growing pains of Title IX, and she became even more familiar with the law and its impact when she went on to serve as head coach for the women’s field hockey team and as an administrator at FDU. Muller has been teaching in Stony Brook’s School of Professional Development program since 2001, focusing on coaching development, athletics administration and college athletics. She has also served on various NCAA committees, including the Gender Equity Task Force.

In all of those roles, Muller says she gained a greater understanding of and appreciation for Title IX, and has been dedicated to making sure anyone going through any kind of administrative training has a strong understanding of the statute and its role in creating and ensuring gender equity in education.

“It’s really critical for educators and coaches on every level to have a good perspective on what the impacts have been,” she said. “Title IX wasn’t created to address inequities in sports, but it really exposed those inequities.”

Many former coaches and administrators agree that Long Island, and the East End in particular, has been ahead of the curve when it comes to supporting gender equity in sports.

Holden said that she recognized right away that Long Island was “very progressive” when it came to athletics for girls when she began teaching there in 1974, after leaving the Albany area.

“They were well organized, and when I started, they were in their second year of offering sports leagues for girls,” Holden said. “They didn’t have states or Long Island Championships yet, but they were on their way.”

Jayne, who began teaching at Pierson around the same time as Holden was starting at Southampton, gave credit to her colleague, fellow phys ed teacher Larry Foden, who she said was never an adversary when it came to encouraging female athletes and offering them the same kinds of opportunities as the boys.

Mary Anne Jules served as a phys ed teacher and athletic director in the Bridgehampton School District for more than 30 years, retiring in 2014. She chose that career path in large part because of the great experience she had as a standout four-sport athlete at Baldwin High School in Nassau County, where she graduated from in 1977. She credited her teachers and coaches there for encouraging her natural athletic ability, and along with another female classmate, she became one of the first female athletes at the school to earn a collegiate sports scholarship, getting a full ride to play basketball at Providence College — a turn of events she said would not have happened if not for Title IX. She ultimately had to decline that offer, because, at the time, Providence did not offer a physical education teaching certification program. Instead, she went to Cortland, where she played both basketball and lacrosse, a sport she didn’t even try until she got to college.

The growing pains that Title IX experienced in the 1970s and ’80s eventually led to a new era in the 1990s, when loopholes were closed, universities and high schools started to fall in line more effectively with compliance, and certain gender norms and ideals that had been culturally ingrained started to fall away. Jayne remembered years in the 1970s and ’80s where she had to battle against “the boyfriend effect,” where certain female athletes would want to skip practice to buy a prom dress, or were getting pressure from their boyfriends to be in attendance and cheer them on at the boys varsity games, instead of prioritizing their own athletic pursuits.

“There was also this idea that if you played sports, you were going to be gay,” Jayne added, pointing out that that kind of bigotry was weaponized and became another obstacle that prevented young women from reaching their potential in athletics.

But slowly and steadily, the protections ushered in by Title IX took effect.

“What Title IX did was increase opportunities for women to play competitive sports, and what’s happened is they’ve gotten good,” Holden said, pointing out that the level of skill and competition on display these days in the women’s final four tournaments in lacrosse, basketball and plenty of other sports, is unprecedented. “Watching them and their skills and the way they play, it’s really appealing to people who want to see good skills.”

Holden compared that to years past, when her parents and those of her peers would come to games to support their daughters, but would often bring their knitting with them while they sat in the stands, because the games were “pretty dull.”

“It’s like the concept of, if you build it, they will come,” Muller said, referring to the famous sports movie, Field of Dreams.

Jayne said she witnessed that effect in the mid to late 1990s, both at the national level, with the ascension of the U.S. Women’s soccer team, and in her own sports programs at Pierson, with players becoming increasingly dedicated, leading to multiple trips to the state tournament, a tradition that has continued to this day.

Organizations like the Women’s Sports Foundation will point out that for all the advances women have earned in education and particularly in the realm of competitive sports because of Title IX, there is still a lot of work to be done. Many women and young girls still do not have equal access and opportunities in athletics, particularly women and young girls of color, those with disabilities, LGBTQ and trans and non-binary youth, and those from lower socioeconomic status. At the collegiate level, broadcast agreements, corporate sponsorship contracts, distribution of revenue, organizational structure, awarding of scholarship dollars, and the general culture all still prioritize high-profile men’s sports like football and basketball. There is plenty of work still to be done, and it is becoming increasingly clear that it will require a more intersectional approach, rather than a strict gender-based approach.

Still, for many, the legacy of Title IX cannot be overstated. That includes Jules.

“When you think of what athletics has done, for men and women, it really has done so much,” she said. “Sports can really give kids the opportunity to make a difference in themselves. I always say that athletics and phys ed are the laboratory of life. Kids don’t even realize they’re learning when they’re on a team — things like how to be on time, how to get along with other kids, how to follow the rules and how to work hard even if you don’t feel like working hard.”

Playing sports, and being given the opportunity to do so, regardless of gender, certainly set the tone for Jules and her life. Not only did it shape what she wanted to do for her career, but it helped drive home the importance of being active for physical, mental and emotional well-being, something she practices and preaches to this day. She credits her commitment to physical fitness with saving her life — two years ago, she was hit by a truck while going for a run on the back roads near her home in Water Mill. She was badly injured, with multiple broken bones, was in a coma for seven days, and even had to have brain surgery.

“If I wasn’t in good shape, I wouldn’t be here,” she said.

The legacy of Title IX, and the way it has impacted the lives of female athletes for decades, is far reaching. These days no one would dream of trying to cut a girls game short to accommodate the spectators for a boys game. When the Westhampton Beach girls lacrosse team took the field at Stony Brook University for the Long Island Championship game on a Sunday afternoon earlier this month, a large number of their high school peers, boys and girls, made the trek to the stadium to cheer them on, and articles about them dominated coverage in this newspaper.

Some members of that team will go on to play lacrosse in college, earning athletic scholarships. Even those who don’t will carry the thrill of that experience with them for a lifetime, and will inspire younger generations of girls to pick up a stick and play. They can’t even imagine a world in which they’d be issued only one uniform for every sport they played, where they’d only play four games in a season while their male counterparts played twice as many, where they’d be expected to sit down for a friendly picnic with their opponent after a game.

Thanks to Title IX, they’ll never have to.