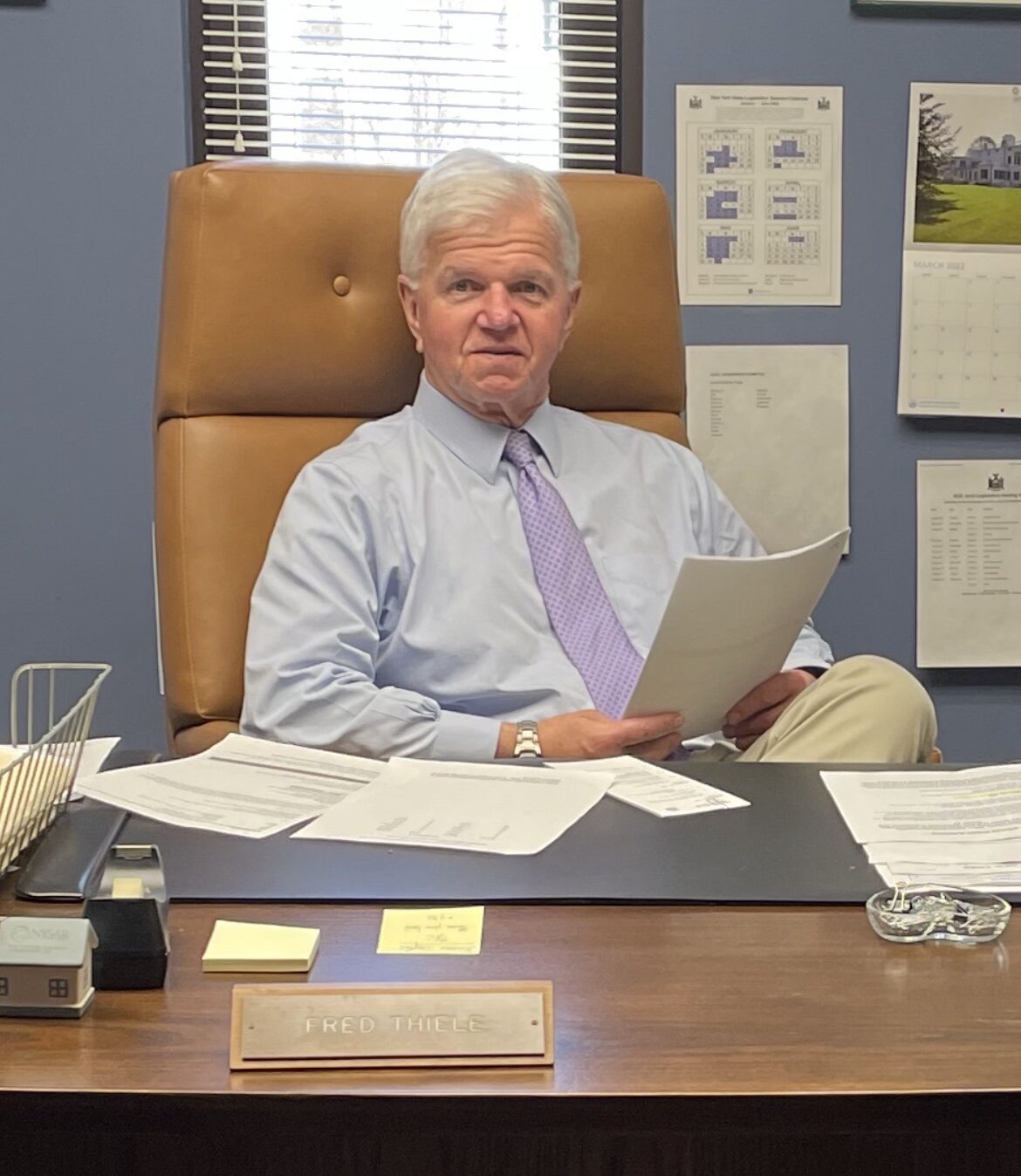

Earlier this month, New York State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr. introduced a package of three bills that seeks to update the state’s school funding formula and increase foundation aid for those in need — a change that some East End districts desperately need, according to their administrators.

But the legislation won’t pass, Thiele said. And that wasn’t necessarily the point.

“I don’t expect that this package will get adopted this year,” he said. “I think it was simply to get the issue front and center, get it on the radar screen, get people talking about it, bring it to our colleagues’ attention that the formula needs to be updated.”

Instead, a line item for $1 million in the Assembly’s proposed $232.9 billion state budget — which must be approved by April 1 — is earmarked for a foundation aid and prekindergarten funding formula study that would allow the New York State Education Department to recommend updates and changes to both.

“It’s just time to fix this,” said Debra Winter, superintendent of Springs School. “I think free appropriate public education is a joke. What’s free about it? What’s free about it? People pay for it.”

According to the State Education Department, foundation aid — which was first enacted in 2007-08 — is the largest unrestricted aid category supporting public school district expenditures in the state. Based on property and income wealth, the formula was designed to require that every school district, regardless of its location or economics, could provide its students with a quality education, Thiele said.

“It’s an attempt to try to equalize different areas of the state so that education opportunities are adequate,” he said.

But the formula was never fully funded, he said, until a concerted effort was made by the State Legislature and the governor’s office starting three years ago. “This budget year will be the year where the foundation formula is finally fully funded,” Thiele said. “It took 15 years to get there.”

As much as this is a milestone, it is also the heart of the problem: The formula is working with “obsolete” figures from a 23-year-old census, he explained. The first bill in the package, “Education Funding Census Update Act,” aims to correct that by updating the census numbers used to calculate certain education funding.

For example, at the Southampton Union Free School District, 60 percent of its student body is nonwhite — up from 45 percent in 2012-13, according to Superintendent of Schools Nicholas Dyno. Its special education population is 17 percent — as compared to 14 percent a decade ago — and English language learners have doubled, from 11 percent to 22 percent, he said.

At Hampton Bays High School, the Latino student population has nearly doubled in just shy of a decade — from 38 percent in 2012-13 to 65 percent in 2021-22, according to the New York State Department of Education’s enrollment data — and English language learners jumped from 8 percent to 18 percent.

“Those census figures that help drive aid are from an era that doesn’t exist on Long Island anymore,” explained Lars Clemensen, superintendent of schools at the Hampton Bays Union Free School District. “There was less need, less diversity and those numbers are outdated, using 2000 year census data.”

The second bill, “Rebuild Our Schools Act,” relates to the apportionment of moneys for capital projects and debt service for school building purposes, Thiele explained, but Winter said that the aid is problematic and not worth the effort.

“I just did a capital project and we didn’t even feel like our building aid would be worth jumping through those hoops to get,” she said. “Building aid is only on classrooms. That’s all I did here, but if you have office space, that’s not in it. If a district builds a garage for transportation, that’s not covered. It has to be classroom space — and we all know you need more than classroom space in a building.”

The cost of construction is, on average, about 20 percent higher on the East End than it is points west, according to Jean Mingot, assistant superintendent for business at the Southampton School District.

“So you have to pay a premium for contractors to come out here and work, and that’s basically for everything. We end up in a situation where we are paying more for everything,” he said. “We’re paying more for gas, we pay more for fuel oil to heat our buildings. We, in some instances, have to pay more to our employees because most employees don’t reside in Southampton — they can’t afford to live in Southampton — so you have to take all that into account when building the budget.”

Despite the Springs Food Pantry serving over 1,300 local families every week, Winter said her hands are tied to apply for certain grants or aid due to lack of parent participation, as well as the Springs zip code being bundled with East Hampton — and its higher property values.

“I cannot state that I have 44 percent free and reduced lunch because they don’t fill out the forms — and why should they fill out the form when I don’t have a cafeteria?” she said, adding, “I think they need to look at the real wealth of our parents, not of the residents that live in the community.”

She sighed. “I’m considered a high wealth district,” she continued. “I am not a high wealth district, I am not. I will fight that to the end. I am not. I’m bleeding here.”

The third bill, “School Aid Equity Act,” speaks to this issue, Thiele said. It would increase foundation aid for school districts in high wealth ratio areas that meet five variables impacting academic success: free or reduced lunch, English language learners, wealth ratio, enrollment and special education.

“I look at that and I think, ‘Southampton,’” Dyno said.

The district is an anomaly on the East End, the administrators agreed. It sits at number one in the combined wealth ratio of districts larger than 1,000 students, Dyno explained, and yet, 47 percent of them are economically disadvantaged and receive free or reduced lunch — as compared to 33 percent in 2012-13.

“So we’re the highest wealth ratio district,” he said, “but almost half our students, our families, are struggling.”

In 2023-24, the Southampton district expects to receive just shy of $3 million in state aid, including stimulus — comprising 4 percent of the total proposed $76.9 million budget — which is down almost $34,000 from last year.

“The district, yes, is well funded by the taxpayers,” Mingot said, “but if we could get the additional state aid to give us more resources, there’s a lot more that we could do.”

In Hampton Bays, now that the formula is fully funded, foundation aid is expected to jump 37.4 percent, or just over $4 million, from $10,738,232 this school year to $14,755,277 for 2023-24. Previously, the district was fourth from the bottom of the list of those that weren’t receiving adequate funds as per the formula.

“The foundation aid catch up was a windfall for Hampton Bays over the last three years,” Clemensen said, “which is why we had two years of a tax levy freeze.”

Even still, it is unclear whether that dollar amount is actually enough — “I don’t have a number of what’s enough, because what’s enough is the definition of foundation aid,” the superintendent said — and that is precisely what needs to be researched ahead of the package’s adoption, he explained.

Mingot called it a “long shot,” raising the question of whether the funds will be redistributed — resulting in some schools losing aid — or if the budget for foundation aid will be increased.

“If it’s the same pie, there is no way that’s gonna pass,” he said.

Thiele said that he expects to see an increase in education funding — “Nobody’s going to get less,” he said — and that the aid will “proportionately go to districts that have the greatest needs” based on the new formula.

“Hopefully that $1 million will be in the budget, and the work that will get done with that $1 million will inform us, as far as actual changes to the formula next year,” he said. “So, again, I don’t expect these bills to pass in 2023, but I just expect them to set the table for policy decisions that we’re gonna make in 2024.”