At age 47, Doris Caridi could see it — the way her retirement would unfold.

In a matter of months, she would give up her apartment in Brooklyn and move into her modest, cozy home in Water Mill, spending her free time with her sister, who lived nearby, and soaking in the bucolic surroundings.

She would mark the end of her 21-year career with the Port Authority Police alongside her closest colleagues, her final assignment being with the Emergency Service Unit at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. There, she reported to Inspector Anthony Infante, who promised to speak to human resources at the Port Authority Police to pin down a target date for her.

That was Friday, September 7, 2001, and Ms. Caridi was happy, she recalled — truly, deeply happy.

“But it didn’t work out,” she said, speaking 20 years later. “And I never saw him again.”

Four days later, Mr. Infante and 83 other Port Authority employees — including 37 members of the Port Authority Police Department — were killed during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, the deadliest strikes on American soil in U.S. history.

They claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 people, from employees grabbing a cup of coffee before work to tourists marveling at the soaring architecture — each of them a mother, or a father, or a brother, a sister, a child.

In Ms. Caridi’s case, some of them were her co-workers, her friends.

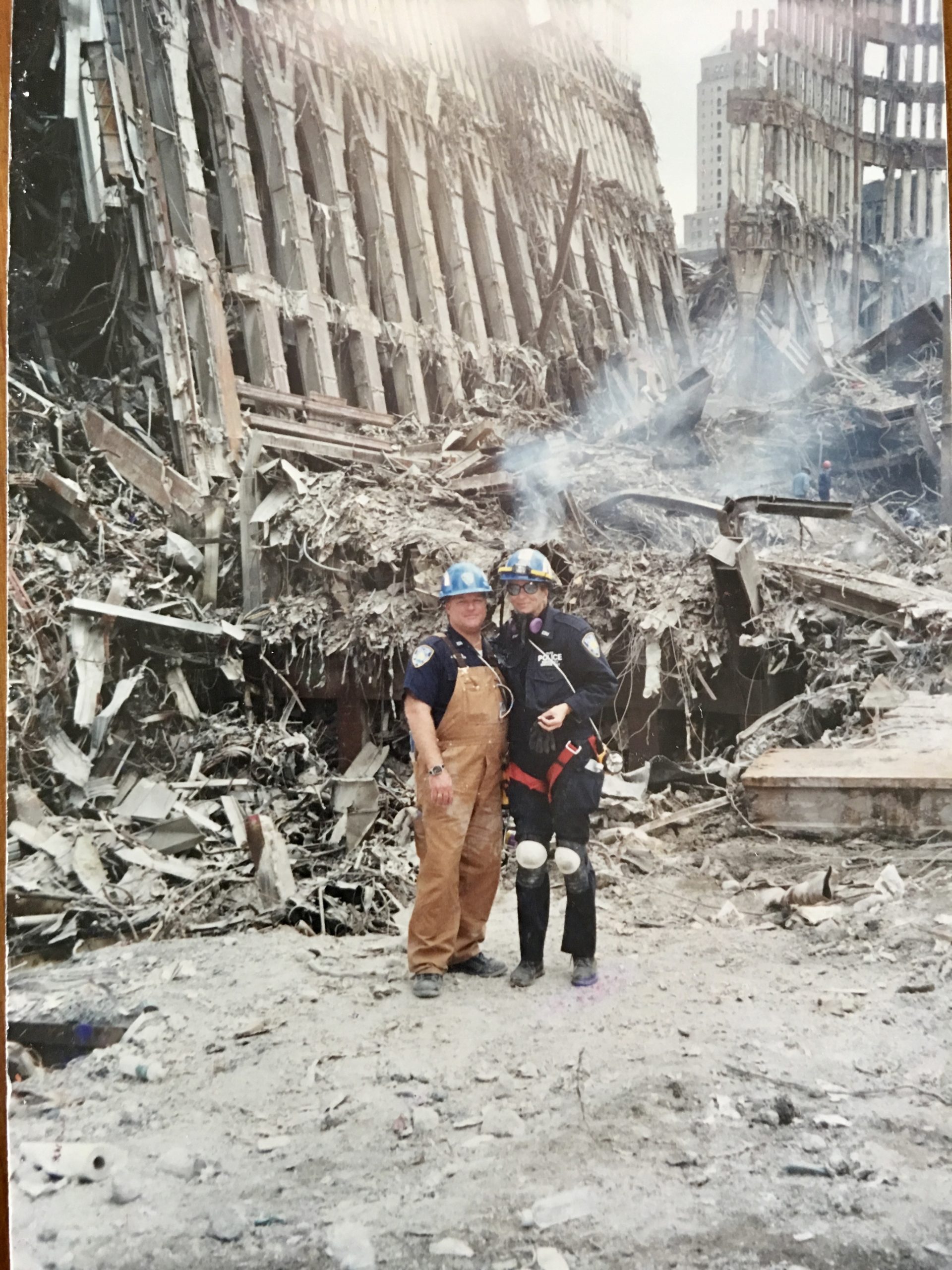

And every day, for the next six weeks, she commuted nearly 200 miles round trip to desperately search for them in what became known as “the Pile” — 1.8 million tons of wreckage sprawling across 14.6 acres.

First, her mission was to find survivors. But soon, that turned to the recovery of human remains.

“The expression that was quoted by Officer Joe Hocker was quite demonstrative of what we lived with all those years,” Ms. Caridi said. “And it was, ‘They died and went to heaven. We lived and went to hell.’”

It was a quiet Tuesday morning in Water Mill — Ms. Caridi was sewing pillows on her day off, with soft symphonic music playing in the background — when the phone rang.

She picked up and heard her mother on the other end. “Turn on the TV,” she said. “A plane just hit the towers.”

At the time, early reports speculated that a small plane had crashed into 1 World Trade Center, known as the North Tower, likely by tragic mistake.

But Ms. Caridi knew better. The campus, after all, was owned, built and operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

“Being that I worked with the planes at Kennedy Airport, and I was well versed with the World Trade Center, I knew the size of the hole and I knew the dimensions of the building,” she said, “so I knew it was not an accident — and it was a major aircraft.”

She immediately jumped in her car and raced toward JFK, joining the mass exodus of emergency personnel from Long Island.

“The state troopers had set up the express lane on the Southern State for us. It had come across on many frequencies that that was your lane,” she said. “Everybody was doing 80, 90.”

By the time she arrived at her command, many of the emergency rescue vehicles had already left. On them were Mr. Infante and her friend, George Howard, a fellow member of the Emergency Service Unit, who rushed to the burning twin towers to help lead people to safety.

When the South Tower unexpectedly collapsed, followed by the North Tower shortly after, they were both killed.

“I don’t talk about that. I never talk about that. I don’t. I really don’t,” Ms. Caridi said, her voice cracking. “I don’t talk about that night.”

It is estimated that over 25,000 people were saved due to the efforts of first responders. But while struggling to complete an evacuation of office workers trapped on higher floors, 343 firefighters and paramedics, 23 New York City police officers, and 37 Port Authority police officers died — along with 2,763 civilians.

And for so many of them, trivial decisions sealed their fates.

“It was all about how you got there — who lived closer, who lived farther, who got on the trucks first,” Ms. Caridi said. “Who went right, who went left? Who lived, who died.”

The next morning, Port Authority police officers arrived back to JFK Airport, covered in dust and debris that they washed off with hoses before setting up a new command post in the Manhattan Community College gymnasium. Huge pallets of water, clothes and food arrived, Ms. Caridi recalled, and at the center of it all was a giant blackboard.

On it was a list of names of every Port Authority employee who was missing — from police and payroll to medical, human resources, and every department in between.

“Initially, when you went in there in the morning, there were a lot of names, because there was a lot of confusion — people who were thought to be dead, it turned out they had gone back to their command,” Ms. Caridi said. “But eventually, the board whittled down to who was actually missing, and those names would be on the board every day.”

She took a deep breath.

“And you’d just pass them and always think today was the day you were gonna find them,” she continued. “But you didn’t.”

Every morning, Ms. Caridi reported to JFK Airport at 5 a.m. — but for the first two or three weeks, she didn’t return home to the East End after her 18-hour shifts, opting to sleep on the floor instead.

She and her team would load up into helicopters, landing in a park near what became known as “the Pile” — mountains of lethal, unstable steel and rubble from the collapsed towers, reaching as high as 72 feet, Ms. Caridi said.

The scene was always a cacophony of noise, with plumes of multi-colored smoke — black, gray, yellow, pink, white — billowing from the wreckage, loose papers flying aimlessly. Dust blew around her boots like snow, the air hanging heavy with the damp smell of concrete and death, she said.

“She changed every day,” Ms. Caridi said, referring to the Pile. “Every day, she changed.”

In the beginning, search-and-rescue teams focused on digging for what they called “voids,” or gaps in the rubble that the collapse created. “They were little holes, little pockets that you had to crawl into,” she said. “They would joke because I was the skinny one, so I could fit into more places. That’s what we did.”

But as the window for survival closed, so did Ms. Caridi’s assignment. Now, she was searching for remains, both on the Pile and the surrounding buildings — collecting bits of body parts, sometimes just tissue, that once belonged to the people thrown from the planes or the towers.

On one such rooftop, her team found scattered airline food trays and a pink teddy bear among the bodies, which Ms. Caridi stowed in her pocket for safe keeping before turning it over to the morgue tent.

“It would matter to someone, one day,” she said. “I thought it was a gift from a grandparent on the plane to a child. I did not want to think it was a child’s.”

In time, the Pile “moved on,” she said, leaving behind nothing — a phenomenon that Ms. Caridi could not grasp, because there simply wasn’t enough recovered to account for all the victims. And so she asked a Port Authority engineer where everyone was.

“Where is Anthony?” she had said, now paraphrasing the conversation.

“Have you seen a toilet bowl?” he responded. “There were thousands in the building.”

“No, not one toilet or desk,” she replied.

“Have you ever stepped on an ant? When you look down, the weight of your body vaporized it. That is what happened to the people,” he said. Toilets, he explained, are just as hard as bone — and, like them, they too were vaporized.

“I just cried,” Ms. Caridi said. “The truth was hard to take. It explained where everyone went. I just could not grab hold of the concept as to, where is everyone?”

Sifting through the Pile on her hands and knees, she stumbled across remains that she couldn’t identify — using a garden trowel to gently scoop them into a bucket, which was then passed down what she called the “conga lines.” More widely known as the “bucket brigades,” thousands of workers passed 5-gallon containers full of debris in a line, much like veins radiating from a beating heart, for investigators to screen, examine and, hopefully, identify.

“It was hard to live under the shadow of our brave men. It was hard to survive and they didn’t,” Ms. Caridi said. “It was hard to be a single woman without children and surviving, and these were a lot of men who had families and children — and they didn’t come home.”

Just before Christmas, sitting on the edge of the wreckage, Ms. Caridi knew the search was over. There was nothing left to be found — any remaining bones dissolved to dust.

Even still, when the Port Authority put out a request for a year-long detail, she was about to sign on, until her sister and brother-in-law came to the Pile to pay their respects.

“He said to me, ‘You really need to come out of here. This place smells so bad, this cannot be healthy,’” she recalled. “And I said, ‘I don’t smell it.’

“I was so addicted to the Pile,” she continued, as she started to cry, “and I was so proud to be there, because I knew that there were, really, millions of people in the country who would have given their right arm to help.

“I wanted to do my duty.”

Ultimately, Ms. Caridi agreed with her brother-in-law and returned to her post at JFK Airport six days a week — only to return to the Pile on her seventh. In March 2002, crews uncovered a lone, 36-foot-tall girder still standing where the Port Authority had installed it three decades earlier.

It became known as the “Last Column,” covered in thousands of markings and tributes by the time it was severed with a cutting torch on May 28, 2002, with hundreds of workers looking on.

Two days later, Mr. Infante’s brother, Andy, drove a flatbed truck carrying the 58-ton steel beam out of the ruins, marking the end of the recovery effort.

Just like that, the eight months and 19 days were over — and, with them, the 108,342 truckloads of debris and 3.1 million hours of labor spent on the cleanup.

“On top of this column, there was a wreath, and on the wreath there was a black ribbon — and I took it and put it in my vest, and I have it to this day,” Ms. Caridi said.

“Andy took the beam to Kennedy and put it in the hangar. Then, in time, we would go over to the ‘beam field,’ we called it. We used to go there in the morning and have our oatmeal before the shift started, and we’d sit on the beams and kind of caress them and talk to them.”

As the years unfolded, the terrorist attacks left a flood of post-traumatic stress disorder among many first responders in its wake. Marriages broke up, alcoholism flared. Ms. Caridi experienced a “massive personality change,” slowly becoming more and more reclusive as she retreated into grief and agony, she said.

A triggering smell or sound would transport her back to the Pile — like when, years later, the beeping of a reversing landscaping vehicle in her neighbor’s yard reminded her of the grappler trucks creating pathways through the debris.

“All of a sudden, I just lost my mind,” she said. “I just said, it had to stop, it had to stop, it had to stop.”

She ran next door and begged the landscaper. “Please stop,” she pleaded. “Please stop that!”

But he couldn’t, she said. It was illegal to disconnect the warning signal.

And so, she had to leave the house every day until the work was completed.

“I started going to therapy, and the therapist was the one who said to me that something of that magnitude and that horrific, unimaginable nature is far too much for your mind to absorb,” she recalled, “and your mind is starting to reject it and flip on you, and you’ve got to take a break.”

The day came in 2006. Ms. Caridi hopped into a truck to respond to a call and started to shake uncontrollably, unable to breathe. After the relief officer stepped in, she went to her locker, collected her belongings, put them in the back of her car and drove out to Water Mill.

And she never went back.

“I put in my papers, I retired, no fanfare — just out the door, goodbye. That was that. I stayed with my therapist for as long as I could, and then that was that. That was the end,” she said. “It is what it is.”

Today, Ms. Caridi lives in Florida, where she loves to paint, take art classes and play tennis, as long as her asthma cooperates. “I take lots of breaks to breathe, but I try,” she said. “I try because I am here and they are not.”

Come September 11, Ms. Caridi will attend a mass service hosted by the Port Authority in New York, after visiting the National September 11 Memorial & Museum the day before. At its center is the “Last Beam,” marked by “PAPD 37” at the very top, in honor of the Port Authority police officers — her co-workers and friends — whose lives were cut short 20 years ago.

“One of the men I worked with for many, many years, he said now with the Afghanistan debacle, the terrorism is gonna skyrocket again and it’s probably the worst place in the universe to be on that day,” she said. “And my attitude is the same as it was then: F--- you. There’s no way I’m not going.”

She let out a sigh. “So I will go,” she said. “I’m taking my nephew, who is 13, and his mother said, ‘He should see a part of what Dee did.’”

Outside of a self-portrait hanging on her wall — which depicts Ms. Caridi sitting next to a painting of the World Trade Center towers in their former glory — not one object hints at the history she lived through and witnessed.

And that is intentional.

“It’s locked in all of our minds. It’s etched in stone. You don’t forget,” she said. “I remember putting everything that had anything to do with those years in this big Tupperware, and I marked it ‘9/11’ and I taped it closed and put it in my sister’s basement.

“And I said, ‘Somebody will want to open it years from now.’ So, there it sits.”