In a 2022 poll of 506 children (ages 12 to 17) and 1,008 parents, conducted by the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland and Ipsos, 71 percent of the children and 58 percent of parents said they knew nothing about Title IX. Those statistics were cited in a report commissioned by the Women’s Sports Foundation, released last month, looking at the history and future of Title IX.

It’s certainly a statute worth knowing.

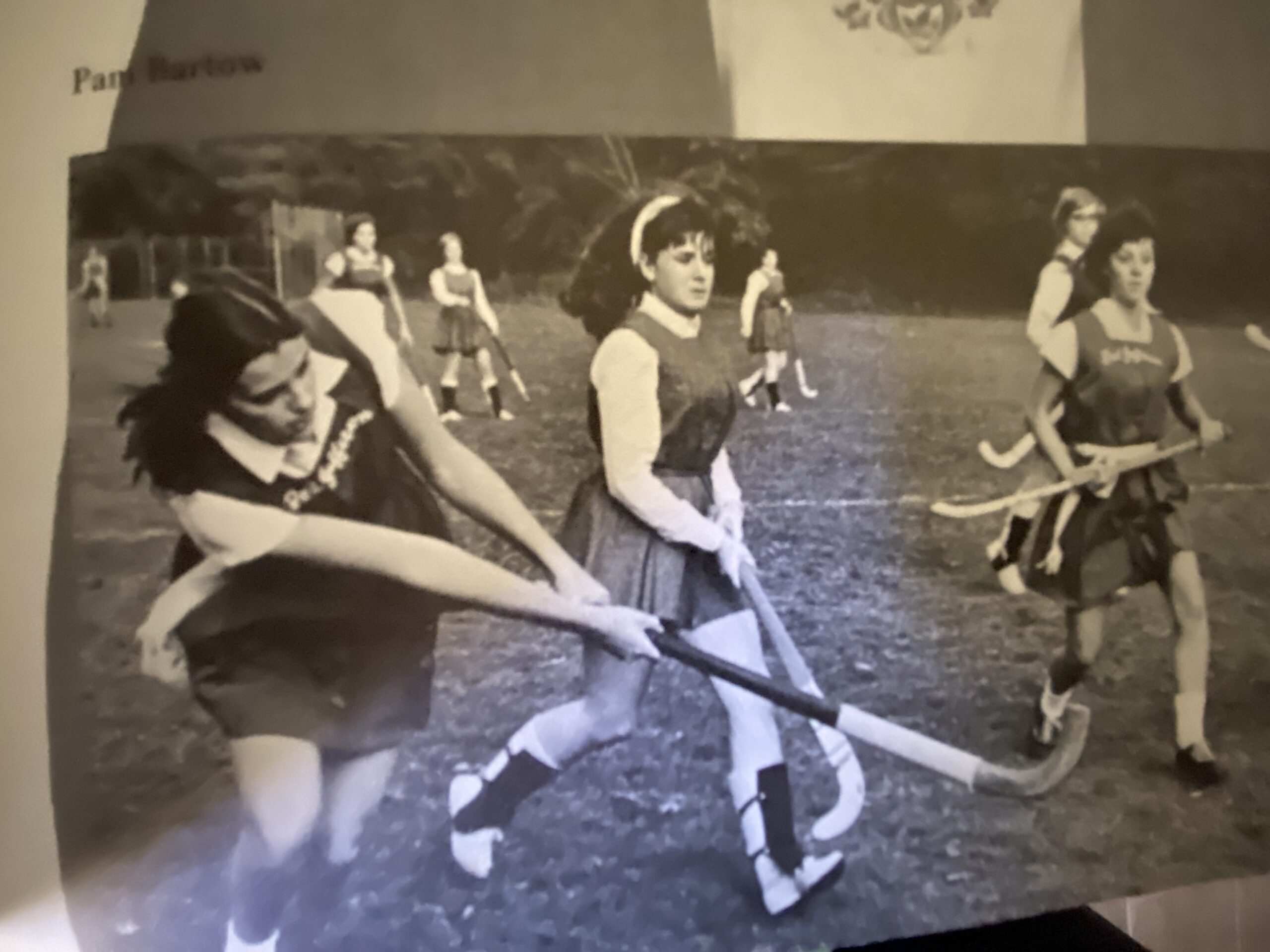

The landscape of female participation in sports — from the youth and high school level, and into the college and professional ranks — drastically changed because of the federal law, although that was not necessarily its original intent.

Title IX was passed in 1972 as an amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and it was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on June 23, 1972. It states that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

It had the effect of expanding access and opportunities for the underrepresented sex — women — in education broadly speaking, helping to pave the way for women to pursue careers that had traditionally been male-dominated and even downright hostile to female participation. It has also been a powerful tool for fighting back against sexual harassment and intimidation in educational spaces.

Of course, the law did not change things overnight. In fact, there was plenty of pushback in the early years, especially when it came to how the law applied to sports.

Colleges and universities went on the offensive in the early years, with the NCAA filing a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1976, challenging the validity of Title IX regulations. The NCAA did not begin putting effort and intention behind creating and supporting women’s athletic programs until after the lawsuit failed, but by 1982, the NCAA finally began hosting its own women’s sports championships in all three divisions.

The court case Grove City v. Bell (1984) created an enormous loophole for non-compliance when it came to gender equity in sports, after it was determined that the law only applied to units in educational institutions that directly received federal funds. Since few athletic departments directly received federal funding, almost all departments in the country did not have to comply with Title IX.

This was the case until later in the decade when Congress passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act. It took until the 1990s for Title IX to have more teeth when it came to enforcing gender equity in high school and collegiate sports. The passage of the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act in 1994, which required institutions of higher learning to annually report data about their men’s and women’s athletics programs, finally created a framework for a greater degree of accountability.

While the notion that participation in competitive sports is only appropriate for men and boys, rather than for women and girls, is, for the most part, recognized as an archaic and outdated approach, and many of the built-in inequities that upheld that old way of thinking have been addressed, staying in compliance with Title IX is still an imperative for athletic directors and other sports administrators throughout all levels of education, and it’s something they must always keep in mind.

Figuring out the best way to enforce, maintain and improve upon Title IX compliance and achieving consistency with creating true gender equity has always been a work in progress, requiring many tweaks and updates along the way. But, generally speaking, for the past few decades, institutions have relied on looking at a “three-pronged approach” to compliance, that is used to measure whether equal access is being provided to male and female students.

According to the Women’s Sports Foundation report, institutions are required to provide “substantial proportionality,” meaning opportunities are offered at rates proportional to enrollment. They must display a “history and continuing practice of program expansion. In other words, they must prove that their program offerings have kept pace with the increased enrollment of females. And finally, there must be “full and effective accommodation,” meaning that the existing number of teams offered “satisfies the interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex.”

The way that looks at the high school level can vary and take many forms. For instance, if a local community member or group decides to donate a batting cage to the varsity baseball team, then it is up to the school’s athletic director and administration to ensure that either the varsity softball team will also have access to that batting cage and that it will suit the needs of both teams, or the district will need to secure funding to build or supply a batting cage for the softball team as well.

That example is illustrative of what has made Title IX so effective: it is not a statute that requires a one-and-done approach to compliance. Rather, it forces administrators and school officials to be constantly evaluating and updating systems and practices to ensure continued and consistent gender equity, ensuring that not only current student-athletes will be afforded the opportunities they deserve, but that the stage will be set — and constantly improved upon — for the next generation of female student-athletes as well.